How can we imagine a society without money, profit, or classes? Recently, I've been wrestling with this question with reference to the problem of the petty bourgeois entrepreneurs, and their social role. This problem is extremely pertinent due to both the volatile politics of this social group today, as well as historically, and the general failure of entrepreneurship and management during the high collective periods of actually existing socialism. The vision of cybernetic economic planning provided by Towards a New Socialism (TANS) is foundational to imaging such a working socialist society, but on this question, it is largely silent. Furthermore, TANS posits a monopoly of all capital (fixed capital and intermediate goods) by the state, and this seems to entrench the problem: making it difficult for new managers and entrepreneurs to arise to best rationalize production and create new products. A monopoly on issuing capital to enterprises could allow for an insider clique to dominate production to an extreme extent. Hence, why I feel the need to write an addendum to this project.

TANS provides a rather rigorous formulation for a way to replace money and private ownership of the means of production with a more effective system. To summarize, a final goods market which accepts labor tokens rather than money is the only market in society. Prices are allowed to diverge from the labor value of the good, when market clearing prices are greater than the labor value, orders for the good are increased to meet demand. Lowering the labor content of goods by using more efficient techniques will also lead to a divergence between labor content and prices, and therefore lead to an increase in orders. Keep in mind, market clearing prices are determined by the quantity of goods supplied vs demand while the labor content is determined by average social conditions of production. Enterprises in the system do not have control over their quantity delivered to market, only the conditions of production. Similarly, there are no factor markets for these enterprises. Instead, input requirements are digitally recorded and changes in final demand orders lead to updated output requirements for all enterprises down the supply chain. An optimization algorithm is used to select the set of raw material and intermediate goods and where to send them in order to most effectively fill the final goods orders.

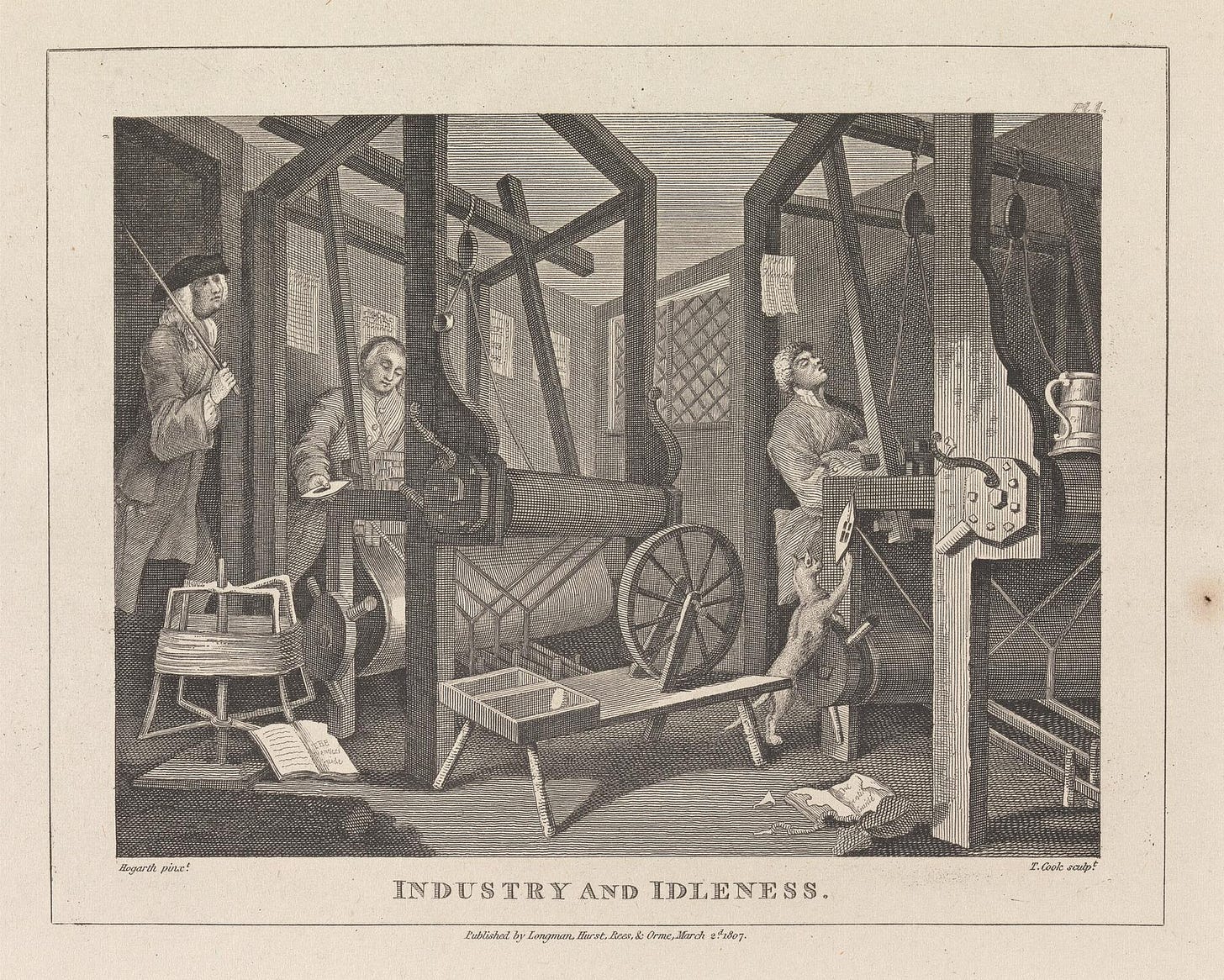

Unlike the Soviet system of material balancing, where quotas and budgets were set in a typical bureaucratic fashion that encouraged enterprises to be as inefficient as they could get away with, this system encourages final good producers to be as efficient as possible in order to get more orders. However, there are some things about this system, which was meant to be a possible outcome of reform to the Soviet system, that retain the legacies of that extremely centralized state system. This relates to the state ownership of all capital, as a means to abolish capital markets. Investment levels in this system wouldn't be decided by private individuals but by democratic decision making. But, whether there is one enterprise in an industry which manages this capital or several, this national state monopoly ensures that a small number of people in practical terms will be able to control access to it. In the ideal of TANS, this could be done by a committee or committees chosen by sortition, but it's easy to see how such a method of control could lead to the system being dominated by a small clique connected to a few very large enterprises or the state apparatus. It makes it difficult for individuals to contribute to the project of developing new goods or new enterprises which is necessary to prevent monopolies from forming, which TANS warns against in the socialist economy. Without competition, after all, there is nothing to compare a producer's use of labor and raw material inputs against, potentially allowing these real costs to balloon out of control. But, simultaneously, TANS proposes that there exist no real independent institutions or enterprises from the national economic planning system, in the sense that the economic planning authorities create and terminate projects according to the requirements of the national plan and their own judgment. Labor and resources are shuttled according to where they are needed according to the plan. The need for competition is somewhat in contradiction to this approach. Let's imagine that the planning authority has created a requirement that 3 project teams be created producing the same type of widget working independently of each other, who does it decide should lead these project teams? Ordinary workers who have worked in related fields chosen at random? A subset of workers with professional management certifications? How does the project performance reflect on the manager?

To illustrate some of the issues here, it's useful to imagine how things might go wrong. Due to the fact this small group of workers are the only ones with experience in a given field, they keep getting chosen for projects in this area, despite not being very competent. Or similarly, a bad manager keeps getting assigned to manage projects because they have the certification that meets the requirements. In terms of issuing capital for the purposes of new projects or enterprises, we can imagine many systems that might work well on paper, but which could easily be perverted on account of control of access to capital itself being monopolized. Imagine, for example, workers in a planning authority conspiring to allocate capital to friends, family, certain ethnic or racial groups, ect, or otherwise figuring out ways to allocate capital that benefits themselves. What system would be structurally inclined to allocate capital to effective managers and organizations based on their abilities?

According to Neurath, or at least the account of Neurath I got in school, there is no difference between a good manager in capitalism vs a good manager in socialism. But of course, an effective manager is nothing without a good team behind them. I do not think it should be controversial to note that developing effective enterprises is not just a matter of rational calculation, it's also a matter of creating good institutions. Here, the birth and death of organizations matters a great deal. Simply having a planning authority arbitrarily create and destroy projects and project teams is probably not as useful as encouraging good teams and managers to form and persist.

Today, existing corporate forms put this drive for creating good managers and teams onto the profit motive and private ownership of firms. But it's possible to think of such a thing without profit or private ownership. Individual ambition will not disappear in a socialist society, and leading a team to become an effective organization should still be a role available to ambitious individuals. If it is the case that the only real organization in a socialist society is the planning organization, then it would become quite fragile. I believe we can take some inspiration from existing government contracting on how to make this work.

Generally speaking, for large government contracts there is a prime contractor, who is directly paid by the government, and a number of subcontractors, who have a contract with the prime. If we assume that the factors of production are owned by a political authority, such as the national state, regional government or commune, a part of the contract with the political authority includes being granted permission to use and maintain this capital. Workers at the enterprise are there by voluntary association, but are paid the same wage as everyone else, and only because they are given access to tasks via the contract. But, crucially, the enterprise is an independent corporate entity. If it loses a particular contract, it will still exist. If it loses all its contracts, it would have to disband due to people needing to take other jobs, but otherwise, it is an institution which can take on different tasks and contracts over time.

Allowing subcontracting makes it possible for entrepreneurs to create new entry level enterprises without permission from central authorities, starting small and gaining experience in management and operations over time. Due to requirements for competition and the fact that enterprises can not choose the quantity they produce, we can imagine a common contract structure for goods where x number of enterprises compete for different levels of order deliveries, where the most productive enterprises get the tier with the most orders, and vice versa, with the number of firm tiers determined by the depth of the demand. Similarly, entrepreneurs can pitch new product development to larger enterprises through this system.

Since communes, as political entities, can hold capital we can also imagine that they can independently contract enterprises to deliver goods or services. If communes are also a corporate form of free association, which they should be, new capital can be created via a process of self taxation and independent labor (for example getting together to erect a building or create a communal set of yard tools). This capital wouldn't exist in compensation with any other capital on a market, but could be deployed as a part of a contract to provide goods or services to the commune members. This makes it possible to create institutions and enterprises spontaneously, without having to worry about approval from authorities even for access to capital.

A common question among leftists online today is whether restaurants will continue to exist in socialism. Well, serving food is something a lot of people aspire to, even if they don't particularly like the grueling and humiliating aspects of the capitalist service industry. Lots of people dream of creating a restaurant of their own and with their own recipes. I don't imagine that aspiration will go away or is inherently antisocial. We can imagine a situation where a commune creates a contract with an ambitious entrepreneur to create a restaurant using capital that the commune has pooled together (buying an oven, pots, pans, setting up the building). The contract stipulates the standard wages for the manager and workers in labor tokens. The manager, even as they control production and the type of cooking, doesn't profit from the enterprise or own any of the capital. But they might create a really great organization for cooking food. If other people take notice, maybe more communes will create a contract with this enterprise so that it may grow. If they decide to terminate the contract, the communes would keep the capital, and potentially make them available to a new enterprise.

For large enterprises and political authorities, we might imagine them operating on a large digital forum where they post solicitations for proposals from enterprises or potential enterprises. A central cybernetic planning system would likely make this process much smoother than contemporary government contracting, by allowing standard input-output expectations to be defined ahead of time, and by keeping records of previous success or failure by enterprises and managers. For an area where there is a large amount of demand, we can expect standard multiple-award contracts in the tiered fashion described earlier. Standardization and simplification of proposals will mean contracting officers would not be required as a specialized profession.

In this way, enterprises are created when a voluntary association of workers receives a contract, and they dissolve when they no longer have any more contracts. Such an arrangement can create institutional dynamism and creative destruction within socialism.

But perhaps even more importantly, it creates a future for the petty bourgeoisie. Today, because of their dependence on meager profit rates, this class is the engine for reactionary politics. And similarly, because there was no place for them in Stalin’s USSR, they ferociously resisted collectivization (not irrationally either) leading to many of the disasters of the 1930s. Socialist entrepreneurship based on a contracting system offers the possibility of a revolutionizing of the values of entrepreneurship itself, and eliminating the reactionary material basis of this class. At the same time, the fragility of socialist economic planning systems would be greatly diminished.

It should also be clear that socialist competition in such a system would be quite different from capitalist competition. This is not a competition, after all, between different capitals, that is, between firms endowed with different levels and types of capital, except to the extent to which better maintenance at one enterprise results in lower levels of depreciation. Nor is it a difference in endowment of other resources. Each enterprise producing the same good gets the same amount of labor and raw materials per unit of goods ordered. Nor can there be differences in pricing strategy to dominate the market, as both the quantity produced and its price are determined algorithmically totally independent of the enterprise as a function of the basic social system. The only differences between enterprises are a difference in quality, and the level to which they apply science to better rationalize production: here is the site of socialist competition.

A socialist enterprise can get ahead, grow, command more resources and earn prestige for its managers and workers, by simply making a better product. Much like in the capitalist world, a first mover advantage will exist with regards to product development, even though there may be higher barriers to bringing a new product to market, or differentiating a product, than in capitalism. A new product, after all, must come with technical production characteristics, expected input-outputs, and a designation code. But whichever enterprise develops a product will be making those things, and be the most familiar with its production process, automatically giving it an edge in the level of efficiency.

For existing products, the battle for quality is largely in the quality of labor and the production process itself. The enterprise that has the best people working at it, which organized production most effectively, and which perhaps works most intensely in the time of the working day (it would be difficult to regulate this beyond obvious excesses), will get ahead.

We can also imagine, for final goods that are somewhat heterogenous (not screws and bolts, more furniture, food, and high level electronics), that the enterprise might be designated on the product, and that orders to specific enterprises might be directly influenced by the judgment of consumers for their quality through their purchases. Socialist “brands” would be nothing more than a different name in the same font type on a box, but this would be sufficient to tell consumers what they need to know.

An entrepreneurial contracting system can also help to overcome lapses in the knowledge of the central planning system, for while input-outputs plans might contain more useful information than capitalist pricing, they might not inherently contain information on where opportunities for synergistic co-production might be. Rather than simply leaving that to formal experts, socialist entrepreneurs may try to compete for synergistic contracts so as to build up institutional capabilities and knowledge in their enterprise.

It is this institutional nature of the enterprise which is largely neglected in TANS, which often feels focused on fending off Hayekian style critiques of planning. When discussing how in the late USSR enterprises were allowed to fail on the grounds they were unprofitable in accounting terms, this was described as a capitalist deviation (indeed it was), but the alternative, which is simply planning authorities creating and canceling projects based on planning requirements and measures of cost effectiveness, doesn't feel much better. Certainly, planning authorities should have the power to create “projects” at will, and destroy them when they are not meeting expectations, but, to return to one of the main questions, it does not deal with at all the criteria for who exactly should work on and manage the project. Allowing projects to merely be expressed as the issuance and cancellation of contracts with independent entities means strong, capable institutions can be built independent of a particular project. Similarly, preventing a monopoly of issuing capital to enterprises, whether through subcontracting or contracting by subnational political entities, will prevent society from being held hostage by a single point of failure in the planning authority.

This vision is also designed to clarify the socialist critique of the petty bourgeoisie, which I have previously elaborated at great length. The antisocial nature of this class, due to its reliance on profits on small amounts of capital, does not tar the socially necessary role of entrepreneurship and organization building. Entrepreneurship, leadership, ambition, real competition, these things are all socialist values. The championing of these values will be necessary to defeat the backwardness, both morally and economically, of this class in the present day.

If you accept the notion of *intangible capital* and *human capital* it's a both alarming and perplexing to claim the state should control all access to capital. But I admit yours is a very idiosyncratic take I haven't really wrapped my head around.