On the rate of interest and oil shocks

What Marx had to say on the general rate of interest, and what econophysics adds on economic shocks.

Whenever one reads the business press, such as Bloomberg or the Financial Times, every piece of news is implicitly framed about how it might impact the rate of interest, which, for the bourgeoisie, may as well be the price of milk or bread. The working class, of course, consumes bread and milk to reproduce itself, and more importantly from the perspective of capitalism, to reproduce their labor power. In comparison, the rate of interest can be taken as the price of money-capital, which is necessary for the reproduction of the capitalist class and capital as a force of production.

Due to the role of interest in determining the return on money capital, the returns to industrial capital have often been framed as another form of interest. While this is a less popular claim today, one can see such claims in the work of important early figures in neoclassical economics, including Mill and Marshal, and there are echoes of it in arguments that profit is the return for risk taking to owners of capital, or as a reward for withholding consumption.

The labor theory of value, in its most elementary form, shows why this is not the case. If we assume that a capitalist has purchased labor, equipment and raw materials all at their market value, such that he cannot make any money on average from arbitrage or market fluctuations, and he employs all these factors of production creating commodities at a given price, he will only create a profit if he produces more commodities than the cost of reproducing all of the inputs. Which is to say, he must employ the labor longer and more intensely than is required to reproduce the workers involved; he must exploit them. It does not matter how much consumption the capitalist withholds, or how risky the enterprise is, if he does not exploit labor.

These sort of arguments are largely fallacious when we talk about returns to money capital as well. For while it’s the case that one can acquire money capital through putting off consumption, or taking great risks, such methods hardly guarantee any returns. Indeed, our recent experience with negative interest rates goes to show that even when saving money and taking risks, the market returns can in general be negative even if all goes according to plan (that is, the bonds are paid out according to what is agreed).

The bond market is a market like any other, in that its prices are determined by supply and demand. This, Marx agrees just as well with any modern economist. But, when we speak of value, we are necessarily speaking of equilibrium, of what the price might be when supply moves to meet demand, thus we are speaking about the laws which regulate the equilibrium, laws which go beyond simple supply, demand and competition. Here, Marx is emphatic: there are no such general laws governing the rate of interest, which is just to say, there is no natural rate of interest.

While there has always been half-baked theories that the rate of interest represents the time-preferences associated with money, from all practical considerations, the interest rate is what economists today call a “policy variable”, which is an exogenous variable set by policymakers. Economic models can model such variables by attempting to create a function which describes how the policy decision is made, but ultimately, it exists outside of pure economic laws.

Marx was heavily influenced by the theory of loanable funds, which says that the supply of money capital is determined by the accumulated savings of society which is put into banks as deposits or directly invested by capitalists, but this is only one example of a more general framework. Today, we know that direct saving is only one small part of the loanable funds in society, which cannot be determined ex ante. Much of loanable funds are created endogenously by banks, who are only limited by legal reserve requirements in creating assets on their books in the form of loans to businesses and individuals. Alternatively, loanable funds can come from central banks, either directly as we’ve experienced through quantitative easing, or through disbursement of hard currency to banks through various means. Regardless of the method central banks use to regulate the interest rate, ultimately, what’s being controlled is the supply of money going into the bond market.

The demand for loanable funds comes from the productive process itself, that is, from firms, who need money capital to pay for expenses. But Marx notes that in times of low interest rates fraud is rampant, since firms are able to get access to money capital for frivolous purposes without much downside, something that we’re all very familiar with for the past few decades.

For prices in other markets, we can assume that an equilibrium will be arrived at based on the costs of production, such that supply will adjust with changes in demand by returning to that price, which is cost plus the industry profit rate. In certain eras, when the monetary supply was tied to mining ore, we can possibly speak of such an equilibrium, but to a large extent, this cost restriction on money capital was unacceptable to capitalism. As Cockshott et al point out in their book Classical Econophysics, the circuit of capital which takes money capital, transforms it into commodities, and then sells those commodities for more money capital than it began with, must have a constantly expanding monetary base in order for macro level nominal profit to exist, as well as there to be a reason for investing in productive capital rather than simply holding cash (something which becomes a major problem in deflationary environments).

In order to avoid deflation and encourage capitalist growth, it was necessary to move to a form of money which was constantly expanding itself, hence the move to fiat. Marx, of course, did not live to see this full transformation, but already, in the days of gold commodity money, he was able to understand the dynamics behind it. Unlike many of his contemporaries who belabored the connection between gold extraction and gold holdings as the central laws behind monetary phenomena, Marx, in declaring there was no general law of interest rates, offered an alternative.

“In the money-market only lenders and borrowers face one another. The commodity has the same form-money. All specific forms of capital in accordance with its investment in particular spheres of production or circulation are here obliterated. It exists in the undifferentiated homogeneous form of independent value-money…It obtains most emphatically in the supply and demand of capital as essentially the common capital of a class — something industrial capital does only in the movement and competition of capital between the various individual spheres. On the other hand, money-capital in the money-market actually possesses the form, in which, indifferent to its specific employment, it is divided as a common element among the various spheres, among the capitalist class, as the requirements of production in each individual sphere may dictate. Moreover, with the development of large-scale industry money-capital, so far as it appears on the market, is not represented by some individual capitalist, not the owner of one or another fraction of the capital in the market, but assumes the nature of a concentrated, organised mass, which, quite different from actual production, is subject to the control of bankers, i.e., the representatives of social capital. So that, as concerns the form of demand, loanable capital is confronted by the class as a whole, whereas in the province of supply it is loanable capital which obtains en masse.”

Thus, when we speak of interest rates in general, for the whole market, we must speak of them as the instrument of the capitalist class in its most social and well-organized capacity, subject to the control of its representatives in the form of bankers.

It is therefore something of a shame that Marx was never able to complete his theory of the state, for if he was, he might have notice a structural similarity here, between the most social and organized form of the capitalist class appearing in the market for money-capital, and that which exists in its most collective form in politics, wielding the state as an instrument of its power, just as it wields the rate of interest as an instrument. The federal reserve, and the increasingly powerful central banks in all developed capitalist countries, is the unity and perfection of the collective, social, and organized form of the capitalist class. Seen in this fashion, it’s easy to see how the apparent neutrality of central bank independence, necessary to achieve its social control functions, is one of the most politically potent aspects of high bourgeoisie power.

Today’s integration of the Federal Reserve with the banking industry, including it’s titans such as Blackrock, shows this explicitly. The history of the Federal Reserve and the banking industry involved in setting interest rates, is a history of the political collective of the capitalist class doing whatever it takes to preserve the capitalist class and its interests. Volcker crushing the labor movement due to its role in the wage driven inflation spiral, helping to preserve profitability in the long term even if it hurt in the short term, the bond activists that brought New York City to its knees in 1975, the decades of falling interest rates to provide businesses with softer budgets, all of it has more or less progressed along such purposes. Regardless of whether or not interest rates are used effectively by bankers and policy makers, (they were used to disastrous effects when the US raised rates in the Great Depression, or when, today, Turkey lowers rates despite its currency crisis), interests cannot ever be a radical progressive force.

We can understand why this is the case if we examine what interest rates are in material terms. Let’s return to the beginning, while interest rates cannot be used to explain profits, we do have to understand interest rates in terms of profits and surplus. The general rate of profit necessarily places an upper limit on the rate of interest. Assuming similar distributions of interest and profit rates, a rate of interest above the rate of profit would entail making the vast majority of economic activity unviable, as any capitalist with access to money capital could get more money from loaning money than making productive investments. What’s more, if profits are less than interest, there would be no way for firms to pay interest except by incurring further debt or drawing down cash reserves. In other words, such a situation is not sustainable.

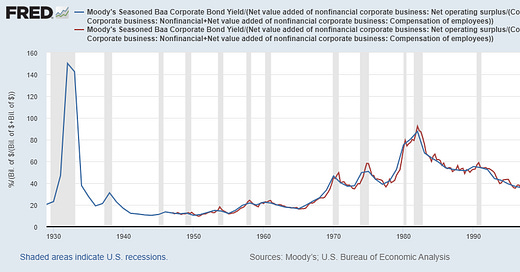

Comparing the ratio of corporate interest rates to profit rates, we can see that the great depression and the Volcker shock had the most severe relationships between interest rates and profit rates, with the Volcker shock being much worse on non-financial business.

Therefore, while there isn’t a law determining the natural rate of interest, there is a natural limit to the rate of interest. Below this limit, the rate of interest determines the distribution of surplus among the capitalist class, differentiating what Marx refers to “profits of enterprise” and interest, with profits of enterprise going towards the industrial capitalist, and interest going to the financial capitalist. Interest appears as an entitlement to the capitalist class, something which it is owed regardless of whether or not production creates surplus value, even though, if such surplus is not created, interest payments would break down. It is, in some ways, the supreme form of capitalist rent seeking for this reason.

Counterintuitively, however, when rent seeking is on the rise, we tend to see falling and low interest rates. The one constant of capitalist economies is accumulation within the capitalist class; even in those capitalist countries where deflation has periodically taken hold, such as Japan. Accumulation necessarily means that loanable funds are increasing, and thus interest rates decreasing. Without destruction of physical capital through war or through a capitalist crisis, we see a regime of overaccumulation, whereby extreme risk taking, speculation, and fraud take hold as the necessary cost of supporting rent seeking financial capitalists. This is not unrelated from Lenin’s observation that imperialist capitalist countries typically lose their industry due to an increase in rent-seeking over time.

One thing that Marx did not grasp, however, because his theory was still operating on the level of ideal representations, of rates of profits and interest at an equalized and general level, was the impact that a changing interest rate would have on the profit rate distribution in the economy. Interest rates changes necessarily have a disproportionate impact on the lower end of the profit rate distribution, for a number of reasons. Firms on this lower end of the distribution face higher borrowing costs because of risk premiums, deal with the threat of being cut off from credit by ratings agencies or banks, and face the possibility of bankruptcy accordingly.

Thus, when we speak of interest rates affecting the economy at any given point in time, we can not simply speak of how the general levels compare, but how rapid is the change, how big might the shock of rising interests be to the profit rate distribution at any moment?

To that end, I created this index of interest rate shocks, looking at the highest monthly year over year change in a given quarter or year, and subtracting that from the general rate.

This index, I believe, directly quantifies qualitative changes in the economy, essentially measuring creative destruction, how many of the existing institutions in our economy are being wiped out. Unlike the ratio of interest rates to profit rates, 2008 shows up as significantly as 1979/80. Pay close attention to where the graph goes below zero.

Such shocks are not limited to interest rates, however, interest is unique in that it is taken as a share of profit, all other price shocks are expressed already within costs and therefore the rate of profit. Price shocks, like interest rate shocks, are first and foremost extreme changes in the distribution of income. Spikes in the cost of oil mean increase in oil rents for the producers, which, even if this corresponds to increased consumption by oil producers (which is unlikely given that consolidating income means comparatively less of that income goes towards subsistence goods), the change in consumption patterns requires time for supplies to adjust. All supply shocks entail a short term decline in output and consumption due to its effects on income and costs to producers. But of course, goods like oil are also consumption goods, which ordinary people also buy. An increase in the cost of oil also leads to less room in household budgets for other goods.

We can gauge this effect on consumption by comparing the cost of oil to worker’s average earnings, see below. The red line represents the recent daily high in oil prices relative to last month’s average wage.

While the price of oil has declined from its peak last week, we should still expect a hit to consumption. I recently saw an absurd dismissal in a Reuters article:

““Household savings could help consumers maintain spending volumes in the face of related price increases," JPMorgan economist Daniel Silver wrote this week, noting that each 10% increase in oil prices would cost consumers an additional $23 billion each year.

Households "have accumulated about $2.6 trillion of 'excess saving' in recent years relative to the pre-pandemic trend, which all else equal could be enough to cover even a sustained 50% surge in oil and natural gas prices for many years to come.””

This is flat out false. Household savings was 1.61 trillion in Q1 2020, which is over 200 billion more than the 1.37 trillion in Q4 2021.

I can only assume that this economist, Daniel Silver, was looking at the annual savings data, which ends in 2020! The money from the covid stimulus checks has been spent and gone.

The truth is that we’re facing a combination of pressures, with more to come when the Fed begins raising rates for real, lacking many other tools to control cost-side, supply-chain related inflation.

By cutting a country as large as Russia from the global economy and the war also disrupting production in Ukraine, we are effectively creating a massive negative productivity shock. Besides oil, food and industrial metal prices are also rising dramatically. Once again, we’re finding ourselves in the odd position of history and politics driving industry rather than the capitalist business cycle driving history and politics, as it did for most of the post-war period. While the profit rate rebound after covid provides the US with some room to breathe, we should expect profit rates to begin to fall this quarter.

We have discussed how bankers and the Federal Reserve form among the most social and organized bourgeoisie. If we are to assume they are more well informed than our JP Morgan Economist here, and they are well integrated into the state, as the central bank sanctions against Russia goes to show, then we might actually see a significant back down on the interest rate hikes. The Fed may have tolerated some contraction before, in order to put down a hot labor market and rising inflation, but it’s now necessary, in its battle against the Russian national bourgeoisie, to mobilize the US economy as much as possible, not just for the US’s sake, but to prop up it’s even more precarious allies in Europe.

I’ll leave with one more graph, which is rather cliche, the treasury yield curve, which has historically predicted recessions. We’ve experienced an extreme tightening in recent weeks, and we should expect the 10 to 2 year yield curve to invert soon if trends continue, especially if the situation in Ukraine doesn’t resolve itself quickly.

I don't dislike Marx, and I think that many of his ideas resonate today, some in a quaint outmoded way, others accurate still. However, Marx was a man of his time and situation. Many of his ideas are so fundamentally flawed, particularly as gross overgeneralizations, that it is astonishing to me that many adherents still are willing to run will-nilly with these ideas.

In the interest of brevity (because this capitalist must soon go back to work exploiting labor ;-) ), I will focus on your paragraph 3 above. In this scenario, the ever-persistent class divide forces the situation to be expressed in terms of the capitalist(s) and the labor. What if...the enterprise in question is a brewery? What if the capital contributions were shared, combined with the distribution of ownership as compensation for labor value. Now, everyone is an owner (capitalist) and labor simultaneously. They all agree to self-exploit, as they must, to generate profit in excess of their labor value. Whether to reinvest (hence becoming unprofitable again) to drive growth (we need to buy more malt, hops, vats and hire more labor/dilute ownership), or simply distribute the excess capital (dividends!), all are in the same boat. Yet, the business entity itself operates to the rest of the market with its internal capital structure invisible i.e. it is not directly relevant to how the company actually operates.

Marx was conditioned by his time to such an extent, that he could not practically see this scenario, so most of his theory is harmed by his uncompromising views of class structure.

That's one example. Last for now: I agree with much of what you said about interest rates (not all), of course labor can/is/will be exploited and that's a bad thing, labor need not be exploited though to operate a market economy efficiently.

Would be fun to chat in person one day, good topics.