Reply to Jehu on the Mass of Profit 2

On measuring the mass of value on society and political ramifications

I was just recently made aware of another reply in an ongoing conversation with the Marxist blogger Jehu, you can read the conversation in order here: 1 2 3 4

To recap, Jehu insists that our estimates of the rate of profit and the mass of profit are all misleading because they are not being converted into a commodity money, and that using the dollar as a metric is inherently misleading as a result.

His position can be summed up with the following quote:

Just to be clear on the point I am making:

In 1948: Hours worked = 99 billion, GDP = $265 billion

In 2020: Hours worked = 244 billion, GDP = $21 trillion

This means:

In 1948, the ratio of GDP to one hour worked was $2.68

In 2020, the ratio of GDP to one hour worked was $86.07

If we accept dollar-denominated figures for GDP as accurate, somehow capital has figured out how to squeeze 32.11 times as much value from one hour of social labor in the last seventy-two years.

NOT use-values, labor value — i.e., socially necessary labor time!

Someone needs to explain how this is possible.

Here, I believe it is possible to outline the fundamental confusion that is at work in this comparison. Previously we’ve been speaking about the mass of profit, but, as the conversation has shifted to the question of GDP, it seems we are approaching the issue of a mass of value instead: what is the total amount of value being created in society as a whole. And, as Jehu clearly states here, the question is not use-values (how many actual material outputs we’re creating).

So, what is the mass of value in society?

In my last blog, I laid out a simple equation for calculating the mass of profit: “the proportion of profit as a percent of total value, and then multiply that with the total hours worked in production.”

Simply put this is

(nominal profit / total nominal value) * total hours worked = mass of profit

If we want to know, on the other hand, what the total mass of value is, we can also see it in terms of this equation.

(total nominal value / total nominal value ) * total hours worked = mass of value

Suddenly it may seem as though I’m pulling something of a trick here. X divided by X will always equal 1, no matter what X is, thus, the mass of value will always be the total hours worked, untouched.

But there is no trick. Marx tells us what determines the magnitude of exchange value is socially necessary labor time expended on commodities. To compare one commodity to another and find their relative value we can see the ratio of the socially necessary labor time required to produce each of them. The mass of profit is the socially necessary labor time expended on the capitalist class, in terms of the investment and consumption goods created in order to reproduce it. The mass of value is therefore the total socially necessary labor time expended in a given moment.

What Jehu points out is that the dollar has indeed depreciated a great deal, 10 dollars buys less of other commodities than it did 80 years ago, including labor. But while the distribution of money may determine consumption and investment at any given moment in time, the overall proportions of average prices between commodities, the exchange value, are determined by the labor time.

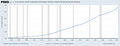

When Jehu says “If we accept dollar-denominated figures for GDP as accurate, somehow capital has figured out how to squeeze 32.11 times as much value from one hour of social labor in the last seventy-two years” he is mistaken on several accounts. For one, the cost of labor has also gone up immensely in this time, indeed, the cost for labor has gone up 32 times as well! And for two, it is wrong to accept GDP as related to a mass of value in terms of social labor in the first place; comparing hours worked to GDP should tell us what the SNLT of present day commodities are, not how much value each unit of labor is creating, which is somewhat backwards. In this sense, the ratios he cites in his post should be reversed as a unit of GDP contains far less labor, and thus less value, than it did 80 years ago.

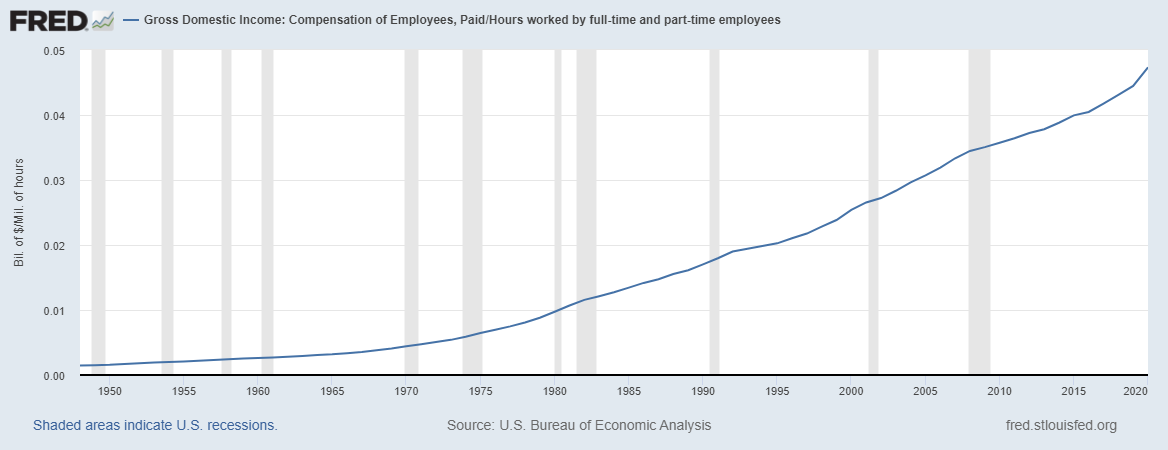

With respect to the price of labor, this is why the rate of profit has not changed much. What has changed is the measure of value, not the magnitude of value itself.

Within a given production cycle, it is necessary to speak of value in monetary terms, as Marx does in many of his examples. A firm might produce $100 more of value by increasing intensity or productivity, but this kind of increase in value is one of distribution - they are taking income away from other firms producing the same or similar good. With a given wage, such changes in distribution mean changes in the distribution of profit, but not a change in its overall magnitude. In a simple reproduction scheme, wages must be sufficient to cover articles of consumption required to reproduce the working class, and surplus must be sufficient to provide for both capitalist consumption and investment goods (the means of production).

As Marx himself says “It is a general law of money circulation that, other things being equal, the quantity of money in circulation increases with a rise in the sum of the prices of circulating commodities, irrespective of whether this augmentation of the totality of prices applies to the same quantity of commodities or to a greater quantity…Wages rise (although the rise is rare, and proportional only in exceptional cases) with the rising prices of the necessities of life. Wage advances are the consequence, not the cause, of advances in the prices of commodities.”

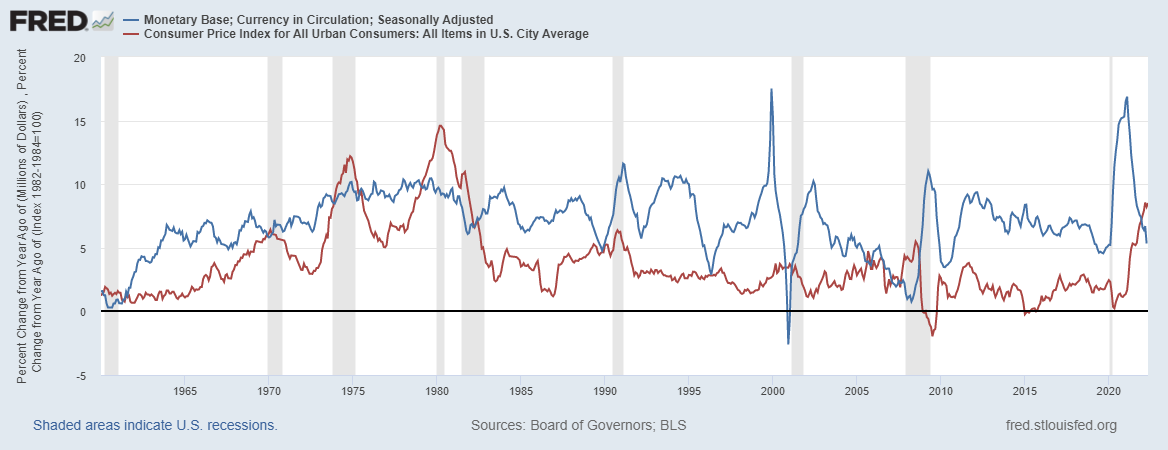

Why have prices risen so much? This is the consequence of one strategy firms take to realize surplus and fulfill the M-C-M’ circuit of production. It is important to realize that this is a consequence of the circuit of capital on a micro, not macro level, as the increase in M is consumed by the capitalist class and isn’t advanced at the start of the next production process. Capitalist firms raise prices to realize surplus, and wages must rise in tandem to reproduce the working class. This entails a depreciation of the currency either through an increase in the quantity of money in circulation or in the velocity of that money. It is this fact which has necessitated our transition to fiat currency. A general rise in prices is equivalent to a fall in the value of money, and now that the value of money is no longer regulated by socially necessary labor time, it is free to realize the surplus maximally.

Though, this does bring an interesting question to my mind. Why is it the case that this surplus isn’t realized in deflationary periods in capitalist economies? Such as in the great depression or in the deflationary periods of the Japanese economy? In times like these the hoard of money that people and institutions keep increases while the amount of money actually being circulated decreases. In these cases, it appears that the value of money rises faster than the level of the rate of profit (which is returned directly to the capitalist), making productive use of money-capital less attractive - the cause of which isn’t a change in the value of money itself, but the previous crisis of overproduction and the resulting fall in prices and profit rates.

Marx said himself, pointing to the lack of correlation between imports and exports of bullion and changes in the prices of staple goods, that it wasn’t the quantity of money which determined prices. We can make the same empirical observation today, given that the changes in the amount of money in circulation do not correlate to changes in the level of prices of a basket of commodities very well at all.

Does a general rise in prices mean the same thing as a general rise in value? Not necessarily. Prices, after all, are just as social as values, and generally speaking, firms will attempt to raise prices as often and as high as they can get away with in order to earn higher profits, prices which, whether they are for intermediary, capital or consumption goods, will go on to be inputs into the next production process further raising costs and therefore prices of final goods.

Labor values serve as gravitational points of attraction for prices as relations to other prices, that is their exchange ratios - not to their absolute levels. With the value of money no longer being regulated by socially necessary labor time expended in its production, these price increases as a method for extracting surplus are allowed to continue at a regular pace. GDP does not represent a mass of value in terms of socially necessary labor time, and at best, by hinting at the number of transactions, real GDP figures hint at how use values are changing over time as understood as a quantity of commodities.

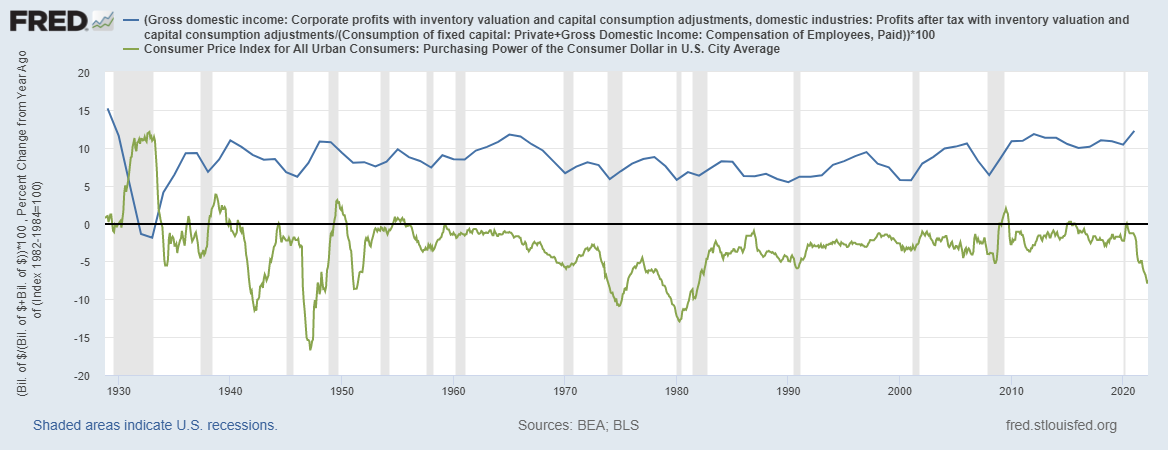

In reality, we can estimate the mass of value over time by using the hours expended in production alone, though a more proper accounting would include a conversion of capital depreciation back into labor hours.

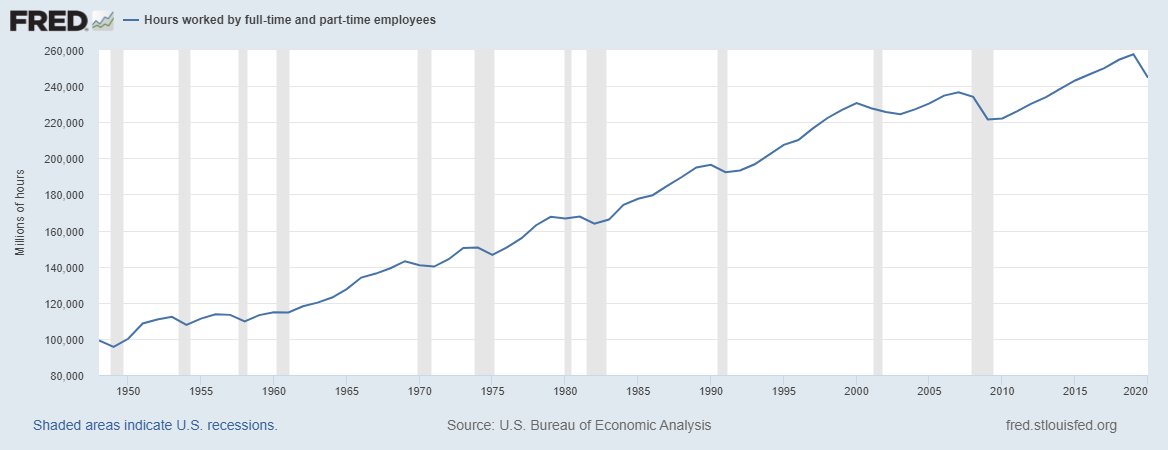

Thus, since 1950 the mass of value has increased in the US by about 240%. Of course, the mass of value doesn’t actually tell us much about the health of a capitalist economy. With a more efficient technical process, firms can produce much more use values with a lower level of socially necessary labor time. As mentioned in my earlier post, it can matter for competition between capitalist powers, but little else.

In terms of a measure of real income, whether of the capitalist or working class, it is still better to look to labor itself rather than gold or silver. After all, everyone has their labor, but only some own silver and gold, and even fewer use it to buy commodities. Indeed, it’s much more likely for people to exchange labor directly for goods and services, than they are to exchange gold and silver for other goods.

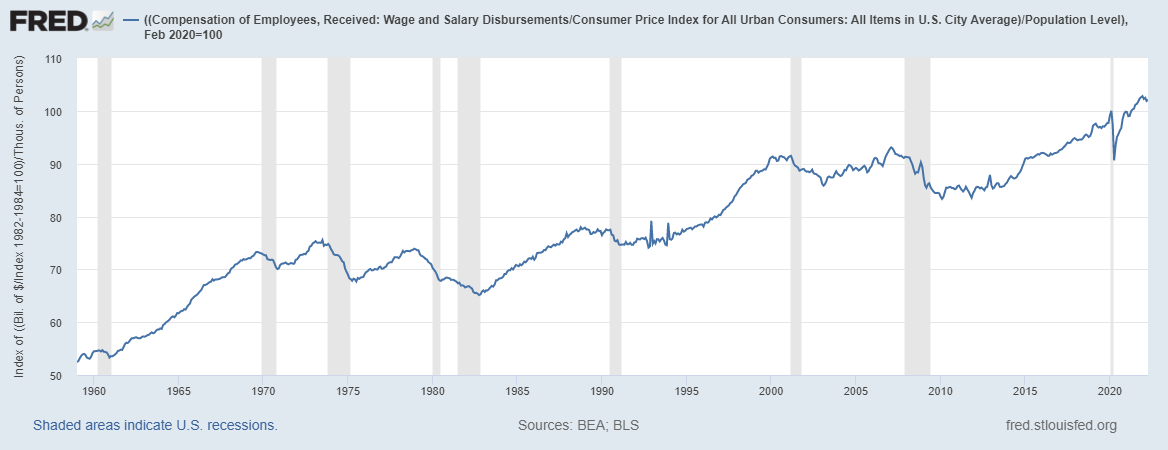

We can do this a number of ways, including using a basket of commodities that can be bought with an average wage, or as a share of total spending. While price indexes created by bourgeois economics are far from perfect, they give us some approximation of these things. My preferred measure for estimating the wealth of the real income of the working class is taking the wage fund dividing it by CPI and then dividing this real wage fund by the total population. I use total population rather than the number of workers because the wages must reproduce the whole working class, including families and everyone else, and with wage labor being the dominant mode of economic relationship I feel this is best approximated by the total population so as to create a historical index.

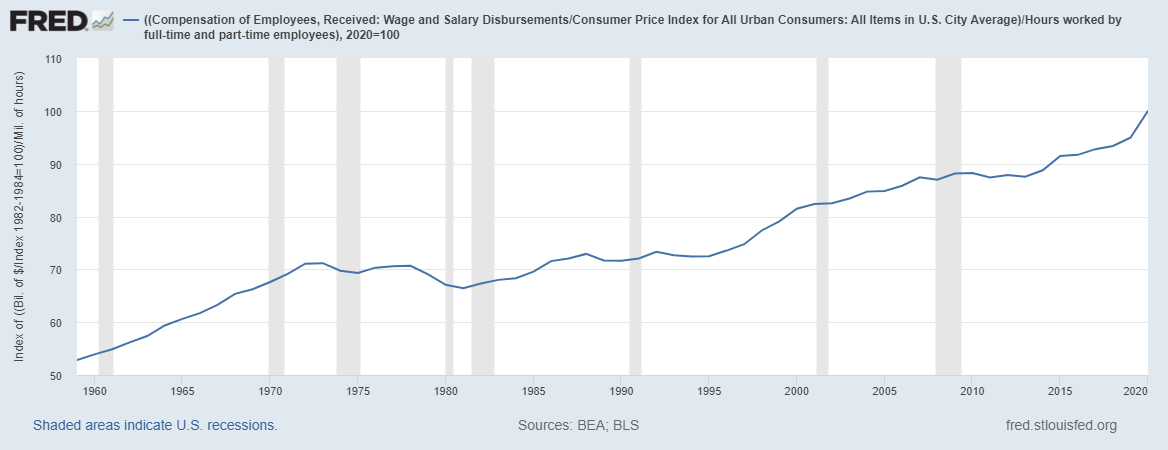

This mirrors the real wage fund per hour expended.

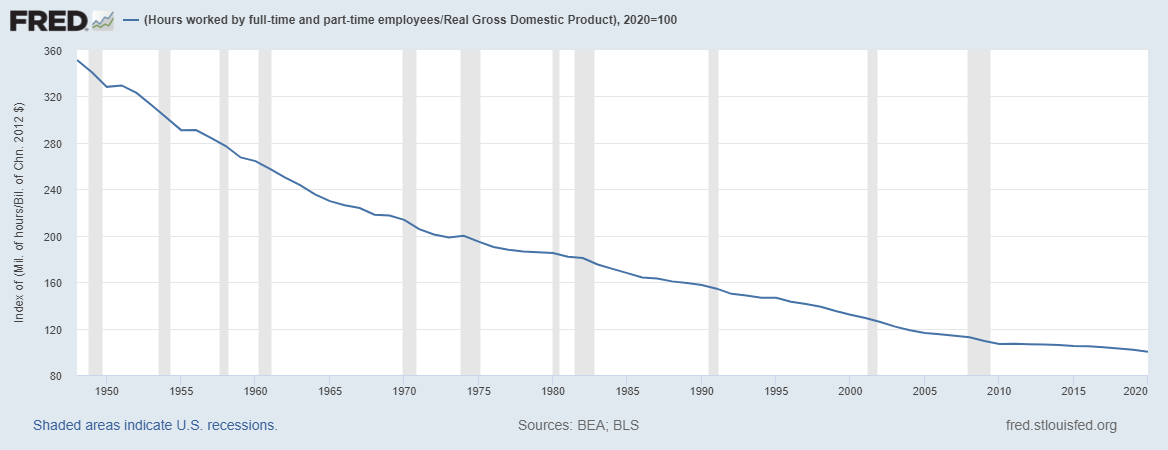

In terms of the value of commodities, we can examine how much socially necessary labor time goes into produce a unit of GDP, which is also a measure of labor productivity. This has a negative trend, which is what we should expect with an increasing labor productivity which is predicted by both bourgeois economists and Marx. The value embedded in our commodities have decreased over time as we’ve produced more commodities with less labor.

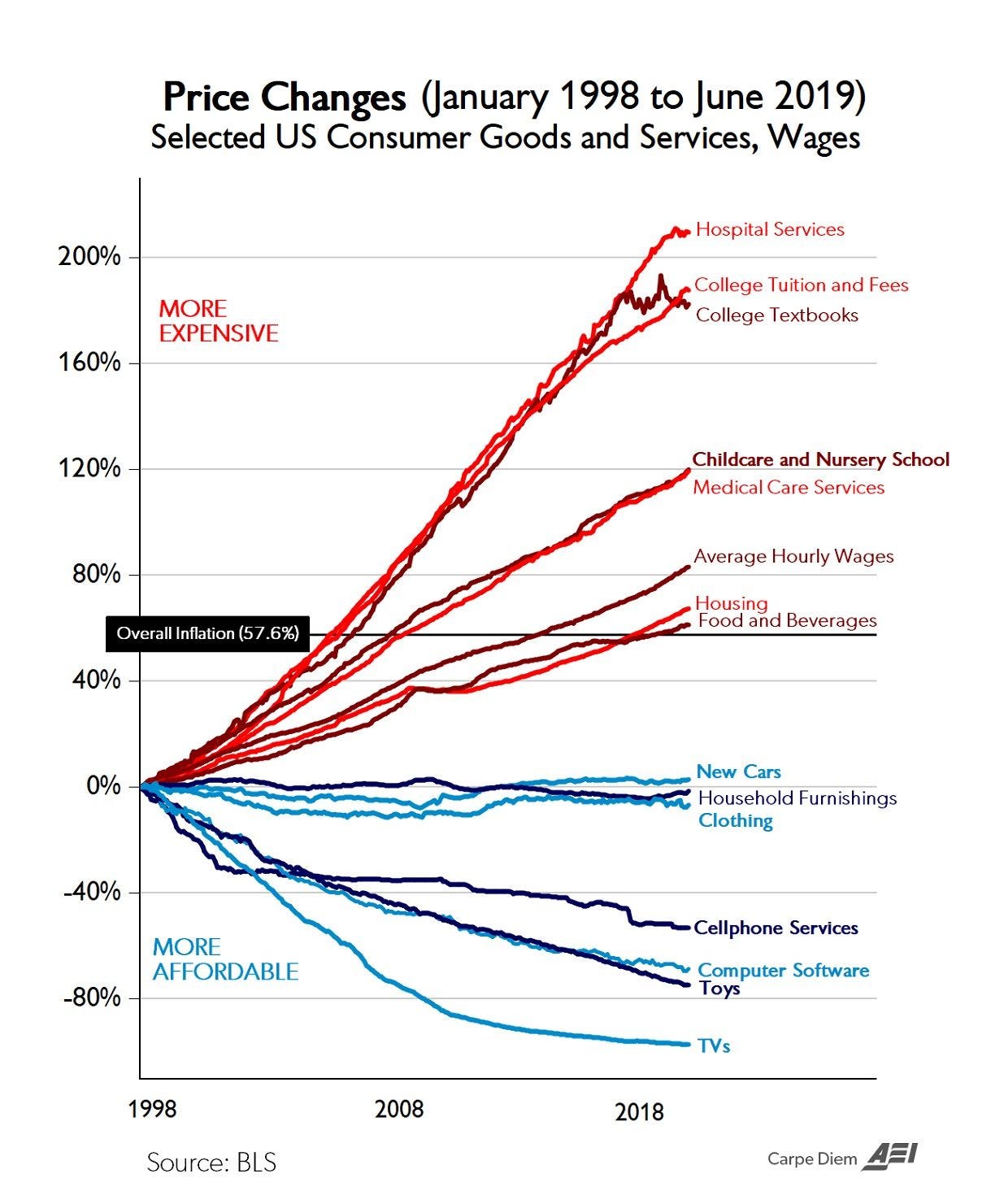

According to the simple labor theory of value, we should expect prices to be going down with less labor content per commodity. And the funny thing is, for goods that we expect are regulated by the labor theory of value, this is exactly what we see.

Most of inflation is occurring in those industries which have not seen productivity gains, and is highest in those industries which are totally rent seeking. For manufactured goods that see productivity gains and lower labor per commodity, prices have indeed gone down.

While the value of rents is not directly regulated by LTV, society must still produce enough surplus in order for rents to exist. Because rent seeking industries have greater purview to increase prices, in a situation of a falling value of money they experience a higher share of surplus.

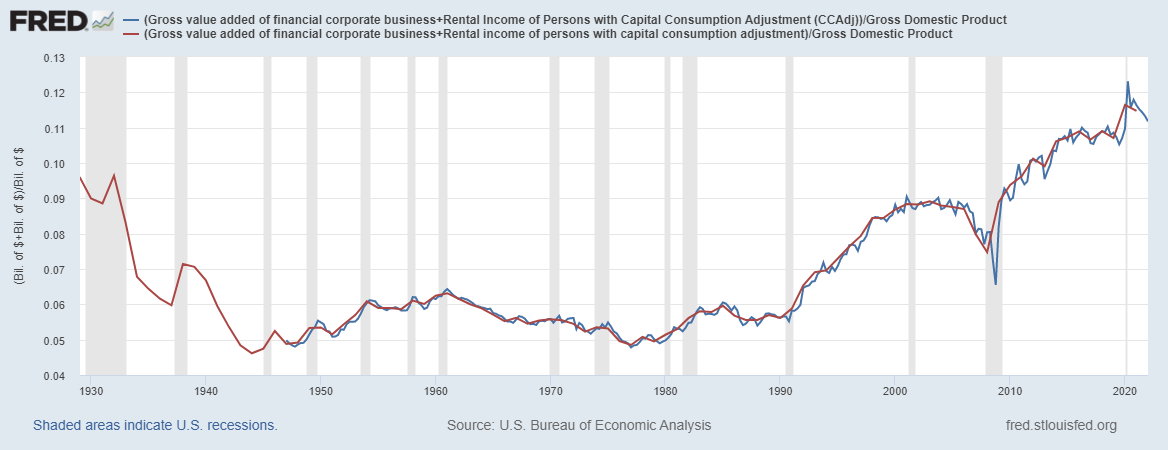

With national accounts this is difficult to measure in its totality, but we can easily see the rents going to intellectual property and to the finance industry. While this shows a dramatic increase since WW2, I believe the true amount of rent seeking is far higher than indicated, perhaps greater than 50%. Indeed, a total historical account may be impossible as whether or not an industry becomes a rent seeking one depends on technical and political changes over time. Only land rents, intellectual property rents and finance profits can reliably be counted.

Regardless, however, increasing rents still demands increasing productivity from productive industries. The physiocrats understood this well, as this literally meant feeding people doing other things besides agriculture.

Given the increasing rent seeking, the increasing population, and the increasing number of commodities in our lives, I simply do not see how it is defensible to suggest that the mass of value or the mass of profit has been decreasing in our society.

In the comment section for Jehu’s response, someone mentioned they were from the Infrared community. At the center of this community is a left wing vlogger, he goes by Haz, who takes a lot of inspiration from, among other things, Xi’s state ideology of the PRC, as well as Jehu’s critique of modern capitalism as measured in gold. Haz suggests that capitalism no longer exists due to the abandonment of the gold standard, see the tweet bellow:

He also cites planning in capitalist societies, along with the abandonment of the gold standard, as evidence we have achieved socialism, and moved beyond commodity production without expropriating the capitalist class. Fundamentally, I believe this position, which is born out of a defense of state ideology, also serves to protect the capitalist class by suggesting that expropriation is superfluous. One thing that convinced me of the importance of expropriating the capitalist class was Jehu himself, when he pointed to me a closer reading of Capital vol 1 chapter 32.

Without a lucid analysis of our capitalist society, we can encourage these deviations that do nothing but coopt resistance to it. This emphasis on gold and this necessary role of commodity money can delude us into believing we are in a better situation than we truly are. Indeed, no doubt this sentiment will explode among the left now that we are close to entering a recession and the stock market is tanking. This optimism about the immanent collapse of capitalism has been with the left since the days of Marx and it has always been misplaced either for economic reasons or political reasons. This optimism is normal, what is not normal, however, is the ways it is being twisted to defend our existing society and the capitalist class.

Considering the scientific deficiencies of using gold as a measure of value today, as well as the reactionary revisionism it encourages, I’d urge Jehu to reconsider his position.