The Tendency for the Rate of Profit to Fall, Crisis and Reformism

A Response to Jacobin Editor Seth Ackerman

Recently, Jacobin editor Seth Ackerman published an essay critiquing Marxist crisis theory and the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, as well as, generally, the idea that crises and the awareness of their inevitability in capitalism can lead to alternative social systems. I believe there are important flaws in his reasoning, including in his technical critique of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall as well as his historical narrative around crisis theory and the new left.

Constant Capital: Income Statement or Balance Sheet?

Many Marxist economists, such as Shaikh, Brenner, and Roberts, to name a few, use capital stock measures to estimate profitability. This is something I’ve called out as a theoretical error in the past, and I think Ackerman’s critique here is a good highlight as to some of the problems with this approach, although I think there are other good reasons to reject the capital stock as the equivalent to what Marx called constant capital in his rate of profit equations.

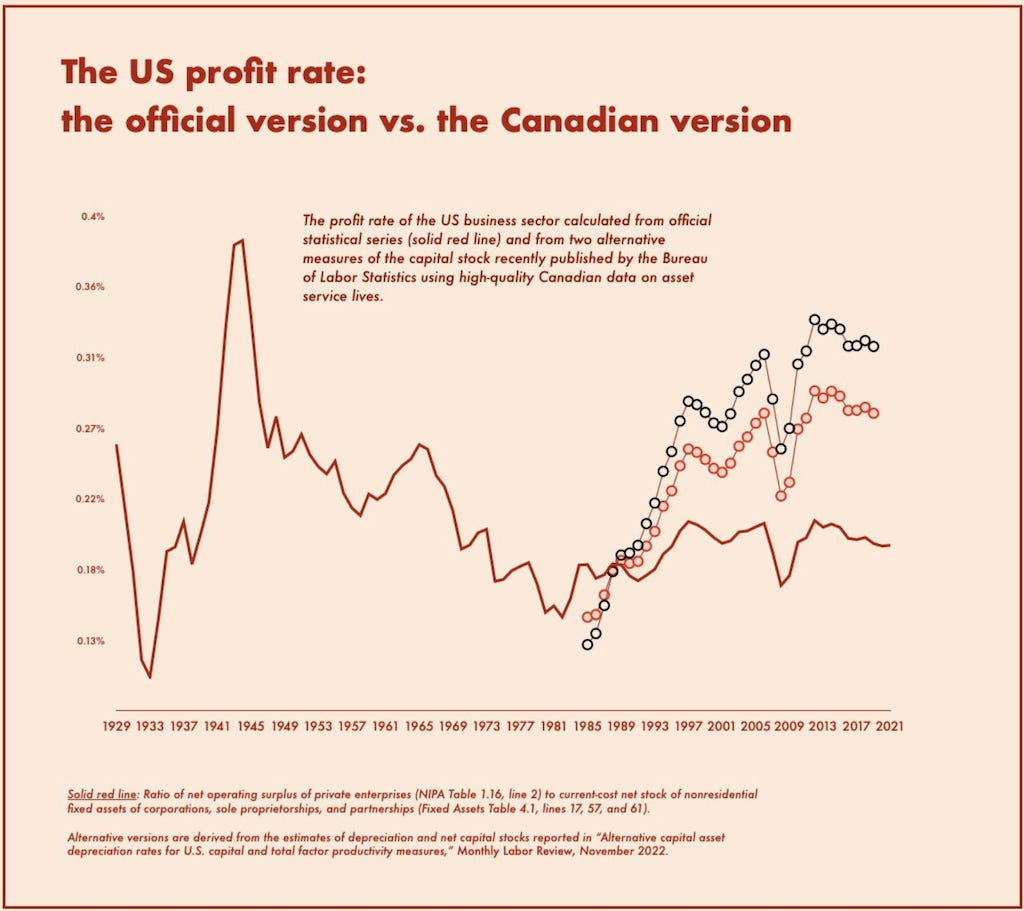

Ackerman points out that different measures of depreciation can radically change the size and trends for the capital stock. He uses the following graph to illustrate this, based off adjusted estimates of depreciation rates. When you have shorter depreciation schedules, capital is used up much faster and the overall stock is much smaller. I will show later that there are technical errors associated with his adjustment, which show that even using capital stock measures, this depreciation adjustment does not provide evidence that contradicts a tendency for the rate of profit to fall. However, for now, let’s just focus on this relationship between depreciation and smaller capital stocks.

There’s a seeming paradox here which goes unmentioned in Ackerman’s critique, but which is mentioned in the paper he cites: depreciation is an expense on capitalist balance sheets, it’s the cost of reproducing the capital stock, all things being equal, a shorter depreciation schedule means higher depreciation costs as you’re having to replace things more often.

With the estimates Ackerman is using, depreciation costs are several hundreds of billions of dollars higher than existing estimates for this time period.

Why is this important? Simple, depreciation, not the capital stock, is constant capital as Marx describes it, and it’s constant capital that Marx invokes when he discusses the rate of profit, which is the equation s/(c+v) where S is surplus, C is constant capital, and V is variable capital (wages)1, or occasionally as invoked by some economists S/C, including Ackerman. The reason I don’t mind this alternate formulation is because it gets at the heart of what Marx suggested by proposing a tendency for the rate of profit to fall caused by rising levels of constant capital.

As for the nature of constant capital as depreciation, Marx explains it rather clearly in his chapter on Constant and Variable Capital in Volume 1 of Capital.

“The labourer adds fresh value to the subject of his labour by expending upon it a given amount of additional labour, no matter what the specific character and utility of that labour may be. On the other hand, the values of the means of production used up in the process are preserved, and present themselves afresh as constituent parts of the value of the product; the values of the cotton and the spindle, for instance, re-appear again in the value of the yarn. The value of the means of production is therefore preserved, by being transferred to the product. This transfer takes place during the conversion of those means into a product, or in other words, during the labour-process.”

“Tools, machines, workshops, and vessels, are of use in the labour-process, only so long as they retain their original shape, and are ready each morning to renew the process with their shape unchanged. And just as during their lifetime, that is to say, during the continued labour-process in which they serve, they retain their shape independent of the product, so, too, they do after their death. The corpses of machines, tools, workshops, &c., are always separate and distinct from the product they helped to turn out. If we now consider the case of any instrument of labour during the whole period of its service, from the day of its entry into the workshop, till the day of its banishment into the lumber room, we find that during this period its use-value has been completely consumed, and therefore its exchange-value completely transferred to the product. For instance, if a spinning machine lasts for 10 years, it is plain that during that working period its total value is gradually transferred to the product of the 10 years. The lifetime of an instrument of labour, therefore, is spent in the repetition of a greater or less number of similar operations. Its life may be compared with that of a human being. Every day brings a man 24 hours nearer to his grave: but how many days he has still to travel on that road, no man can tell accurately by merely looking at him. This difficulty, however, does not prevent life insurance offices from drawing, by means of the theory of averages, very accurate, and at the same time very profitable conclusions. So it is with the instruments of labour. It is known by experience how long on the average a machine of a particular kind will last. Suppose its use-value in the labour-process to last only six days. Then, on the average, it loses each day one-sixth of its use-value, and therefore parts with one-sixth of its value to the daily product. The wear and tear of all instruments, their daily loss of use-value, and the corresponding quantity of value they part with to the product, are accordingly calculated upon this basis.”

This description certainly sounds like depreciation, and in a footnote a capitalist is even quoted speaking of it as depreciation. Constant capital is, to Marx, first and foremost a part of value, which can be equated to revenue and the streams of income it generates, certainly this is how Marxist economists like Kalecki conceptualized it. However, in classical political economy there is some muddling of income statement and balance sheet concepts: value theory, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx was a theory of how a vast accumulation of commodities (a kind of asset) were the wealth of a capitalist economy, and the value of these commodities was explained with a theory of income to the different classes in society. Which is why, in volume 2, Marx can make statements about how hoarded money, which obviously is only an asset and not anyone’s income, is still a part of surplus value.

But there’s no need to resort to marxology here, there are many reasons to see depreciation as the superior measure of constant capital and as a component of the rate of profit. Some reasons we’ve already mentioned: the difficulty of measuring the capital stock, the fact that depreciation is counted as an actual cost on income statements. The underlying logic of our analysis matters too: if wages and profit are both income categories, why should we be measuring them against asset ones?

This is a practical matter, which actually relates to the same issue of the nature of value. When we sell a commodity, such as a banana, this is an asset on the banana company’s balance sheet which is being converted into income. But not all assets get converted into their book value’s equivalent in income. Prices and market demand can change. Much like the tools and machinery Marx mentions, the banana has a use value whether or not it is sold, but it only loses its exchange value as its use value goes away, whether by becoming overly ripe or being eaten. The process of valorization, is the process by which a banana is sold and contributes to the income of various classes in society. If the banana goes unsold and loses its use value, its actually counted as a depreciation cost for the capitalist associated with maintaining their inventory, an earmarked portion of capitalist income which goes to reproducing their stock of capital. If it is sold, it is still counted as income to the capitalist, however now counted as the portion which they can themselves personally consume or use to increase the capital stock above its existing level with net investment.

If a bunch of people bought and sold the banana for about the same price, it wouldn’t increase the value in society, or the income to the various classes, anymore than the original sale, as the income to capitalists would simply equal their non-labor costs, and capitalist income is necessarily surplus, or net income, the income after costs. As I’ve discussed previously, the income which is earmarked for depreciation is also available to capitalists, and they can consume it if they allow for net negative investment levels, however this undermines their structural class role as capitalists. For their part, workers straightforwardly receive wages. Added together, theoretically, s+c+v we get all the income in the economy.

Hence, when we decompose total income, or total value, in society, down to the income of social classes, we can arrive at the apportionment of real resources in an economy. To the extent hoards of money can affect the distribution of resources, it’s only as they change spending and consumption. Total Income = Total Consumption, after all, one man’s spending is another man’s revenue.

For capitalists, the real cost of their income isn’t all the dead labor of ages past. They have concrete costs today, in the now, if we abstract away debt and interest (which is still important for crises of circulation), we can see this clearly. Depreciation represents the living labor which must go back into reproducing the means of production today when we understand it as a part of gross investment. When we compare surplus to wages and depreciation, we see the current rate of return for a given time. If we wanted to see the rate of return of an asset, we’d have to look at the income it can generate over its whole lifetime, much as capitalists do when they underwrite an investment. After all, when looking at the return on an asset, higher returns in some years can actually make up for lower returns in others. But this is necessarily a speculative activity, and, when viewed retrospectively, doesn’t even tell us all that much because income at different points in time can be equivalent to very different levels of real consumption. Not to mention, trying to get returns on assets historically is a much more difficult empirical task, and necessarily abstracted from a single production period.

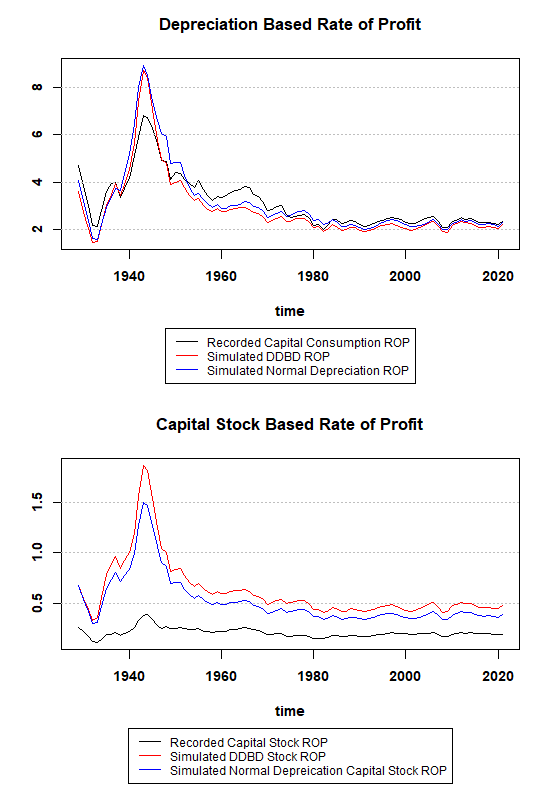

It’s for all these reasons I reject rate of profit measures based off the total capital stock. Previously, I’ve generated graphs such as the following, with depreciation based measures of constant capital.

While higher profit rates than the graph Ackerson presents as the official statistics, the trend is quite similar, however this is a rate of profit measure that includes wages. To truly compare to the original chart, we need to see the rate of profit as a ratio of surplus to constant capital.

This is a fascinating chart, in that it indicates that the return on reproducing the capital stock is roughly the same as it was during the Great Depression and the 2008 financial crisis, and the only reason the total rate of profit isn’t that low is due to a greater rate exploitation during the neoliberal period.

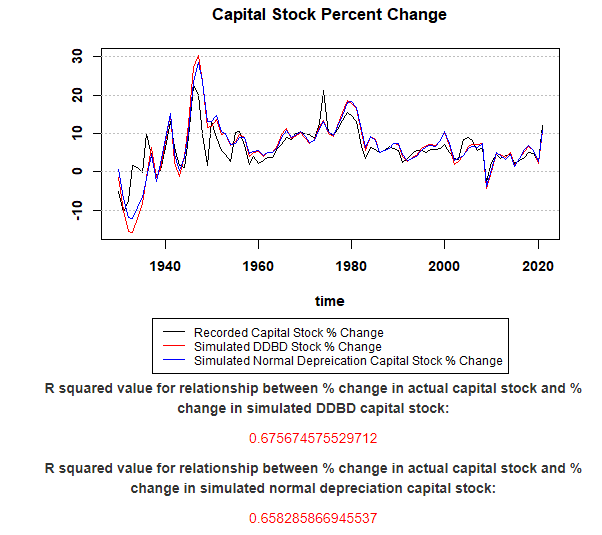

When it comes to studying depreciation and the capital stock, what matters far more than estimating the absolute size of the capital stock is estimating how it's changing over time. If we know nothing else besides the level of investment, we can come up with estimates for depreciation and the capital stock by creating an estimated depreciation schedule filled each year by the investments made.

This is exactly what I did with US investment data, using a simulation I wrote in R. You can interact with this simulation here, it allows you to adjust the length of the depreciation schedule to see how the different variables change, the code behind it can be found here.

There is a heroic simplification in this kind of simulation, which only has one depreciation schedule for the whole economy, while in reality different sectors and types of assets have very different ones. This is likely why my estimate for the capital stock is quite different than the official one when assuming a depreciation schedule of 10 years. A 10 year depreciation schedule, however allows us to closely approximate the official level of depreciation and is a standard schedule for many machines and equipment.

We can also see what profit rates these different measures would produce using the same S/C formula Ackerman used.

More importantly, we can look at percent changes in our estimates of the simulated capital stock compared to the recorded capital stock. This tells us how accurate our model is at estimating changes in the capital stock according to investment data alone.

The R squared value tells us how much variation in the actual capital stock can be explained by changes in our simulated values. To see if our model is actually providing us extra insight over what’s contained in our inputs, we can compare this R squared to the R squared we get between the relationship of changes in the stock and changes in raw investment, which comes to .43.

One reason the R squared for this simulation isn’t higher is because the capital stock is measured with current values, not historic values, thus it changes with the prices of the underlying assets. If we add in inflation data to our model to adjust the value of the capital stock, we get more accurate results.

Knowing how to estimate changes in the capital stock is useful because it tells us whether current actions are undermining the material infrastructure in society through neglect, or actually expanding it.

Now that we’ve gone over these basic issues regarding the capital stock and depreciation, let’s dig into the mistake at the heart of Ackerman’s critique of the rate of profit.

The Technical Error in Ackerman’s Rate of Profit Adjustments

What Ackerman is contending is that the official recorded capital stock and depreciation measures aren’t accurate and that depreciation is actually much higher than recorded, with many assets having shorter lifespans than US statisticians estimate. Fortunately, our simulation allows us to see exactly what happens if we adjust the length of the depreciation schedule for the whole economy.

Since many studies suggest that depreciation occurs at geometric rates, including the ones Ackerman cites, we’ll use the double declining balance depreciation rate, which is also the metric most closely aligned with official records. Let’s compare the rate of profit we get on capital stock measures when we use a 5 year depreciation schedule vs a 15 year depreciation schedule.

While we can see there is a bigger recovery in the rate of profit in the shorter depreciation schedule line since the 80s, it actually has a stronger tendency for falling profit rates over all. How can we reconcile this with Ackerman’s graph, which shows an incredible recovery back to WW2 levels of high profitability? If we go back to the paper where he gets his data from, it becomes clear what the issue is.

As I mentioned before, this paper, “Alternative capital asset depreciation rates for U.S. capital and total factor productivity measures”, puts forward alternative depreciation rates that are higher than official rates. It uses these new measures to create a new estimate for the capital stock, and this is where the issue lies, not in the level of depreciation rates, but how they are used.

As we can see in the chart above, all the estimates for the capital stock begin at the same level, and then diverge. This is because all that’s been adjusted is the flow going out of the capital stock, rather than the capital stock itself. The capital stock, however, is determined by previous flow levels, so by using the official capital stock level and then applying a new outflow level, this basically has the effect of showing a change in depreciation rates. But the paper, and Ackerman, are not claiming that the capital stock is changing because of a change in depreciation rates, but rather that depreciation rates are different overall. This basically creates an illusion when applied to the rate of profit: the rising profit rate is nothing more than the capital stock adjusting to a new depreciation rate, an artifact that would go away if there was enough time.

Essentially what Ackerman has done in creating his adjustment is draw a line between two different rate of profit estimates with different depreciation schedules, switching horses midstream.

Now, this is going to be an inevitable problem for any measure of the capital stock, as at some point your data just drops off and you won’t know what dynamics went into it before that point. Any estimate you start with will be adjusting to the new rules and assumptions you’ve made going forward. In my own simulation, the beginning is always the least accurate and most finicky for this reason. The longer the length of time you’re examining, however, the less of a problem this becomes. In this case, Ackerman’s adjusted rate of profit statistics simply don’t provide evidence for a lack of a tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

I should note, however, that rate of profit estimates that use depreciation instead of the capital stock for constant capital sidestep this issue entirely.

Crisis Theory and Crisis

The deeper political contention of Ackerman’s essay is that crisis theory is a kind of dead end as it relates to politics, specifically the hope that capitalism is unreformable and therefore socialism inevitable. One name that gets mentioned in passing among the history of crisis theory is Henryk Grossman, however there are a number of important details the essay selectively leaves out.

Grossman was, after all, at one point a member of the Frankfurt school, which was hugely influential among the new left. He was kicked out for exaggerated accusations of Stalinism. However, the real divergence between Grossman and the rest of the Frankfurt school, especially what it would become after WW2, was on the question of crisis and the internal contradictions of capitalism2. Contrary to Ackerman’s analysis, which focuses on the minutia of various marginal sects, the new left was more dominated by critical theorists such as Marcuse who believed that the internal contradictions of capitalism had been solved. Far more popular than old school Marxism was various attempts to find alternative revolutionary subjects who could destroy capitalism through other kinds of contradictions. Anti-colonial movements, radical feminism, the civil rights movements. These movements succeeded in securing bourgeois rights more fully to everyone, whether people in the developing world, women, African Americans, but the questions originally raised by the communist movement, of the toiling for a capitalist ruling class, of the destruction of society at the hands of capital, these things remain unanswered.

When the profitability crisis of the 1970s occurred, the new left at large was caught totally unprepared. Without a horizon beyond capitalism, with only reforms available to them to manage capitalism, it became inevitable that the solution would be increasing exploitation and the destruction of working class power.

Ackerman seems to suggest that capitalism did reform its way out of the profitability crisis, meaning capitalism survived while maintaining growth and employment. But, it seems clear to me that the 1970s show exactly how unreformable capitalism is, and the limits of social democracy. It represents a hard limit that capitalism cannot move beyond, which requires either the expropriation of the capitalist class or the liquidation of the working class as a political entity.

To show exactly why this is the case, let’s take a slightly different perspective on the rate of profit. Throughout all this discussion, for various Marxiological reasons, we’ve been focusing on the rate of profit as a relationship between surplus and costs. But, as I’ve mentioned previously, depreciation only exists as a really existing demand on resources to the extent it is a share of gross investment. Knowing how the capital stock is changing is useful for a host of reasons but let’s focus on gross investment for a moment.

Gross investment in fixed capital is essentially determined by technical requirements of production and competition, so long as there is competitive pressure to do so, capitalists will adopt the most efficient techniques socially available. But this also means that, so long as there is competition, the amount of surplus they can actually consume personally is limited by what they have to invest. Capitalists, much like the working class, must reproduce themselves by buying the goods which are required both biologically and socio-culturally. Unlike the working class, capitalists don’t reproduce themselves by selling their labor power, but by advancing the money to buy the means of production and labor. This means that for the capitalist class as a whole, how much money they advance in a given production cycle relative to their surplus is the cost of acquiring that surplus, and the less surplus they get for a given amount of investment and wages, the less individuals can actually reproduce themselves as capitalists.

Therefore, one key metric we can look at is a profit rate that subtracts net investment from surplus, and looks at this consumable surplus as a ratio to gross investment and wages. This surplus which excludes net investment is essentially the surplus which is valorized as consumption goods by the capitalist class. Looking at this profitability metric tells us a very different story.

From this perspective, the late 70s represented an existential moment for the American capitalist class. In 1929 they could earn 50 cents on the dollar for their investments, fast forward 50 years in 1979 and they were making 21 cents on the dollar. This means a capitalist would have had to spend nearly 250% more, not even accounting for inflation, in order to get the same magnitude of value for themselves.

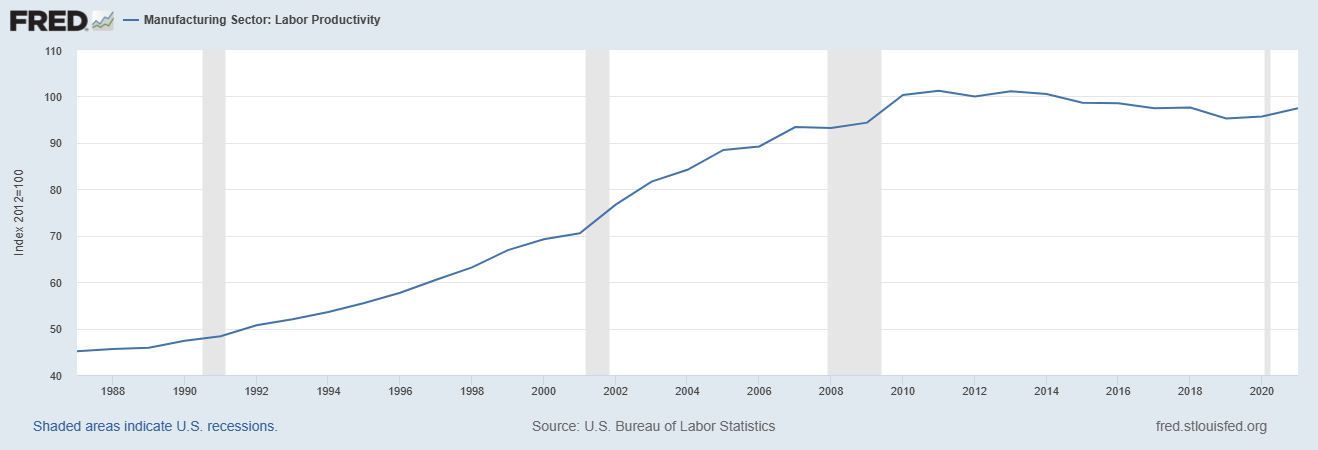

The neoliberal era has eased some of this pain, but it’s important to see how exactly. Ackerman mentions how price wars aren’t really so much of a thing, but that wasn’t always the case, in the period of intense industrialization, the era when profit rates were falling precipitously, it was quite common. We still see this today in manufacturing industries, which is why things like TVs and other household electronics keep getting cheaper. Practices designed to ease competitive pressures, such as world-historic easy money policies that began after the Volcker shock, banking deregulation, increasingly low interest rates, bailouts, and greater labor discipline, all worked to ease the budget discipline of businesses, and its this easing of competitive pressures that has also caused a stagnation in investment.

The ratio of capitalist consumption to gross investment has essentially stayed flat in the neoliberal period.

This is problematic for capitalism because it’s this investment in machinery and new technologies which actually makes capitalism more efficient, dynamic, and improves living conditions, this creates the material infrastructure. As Ackerman notes, the profit to investment ratio has risen in favor of profit. This is the real stagnation, which takes hold specifically in late imperial and developed countries. Indeed, without a rising rate of exploitation, the rise in capitalist consumption would have come at the cost of net negative investment, and the destruction of this infrastructure, as happened in the great depression and world war 2.

Here is the necessary connection between the tendency for the rate of profit to fall and stagnation: so long as investment is rising as a share of non-labor income, all else being equal, the rate of profit will fall. That is, so long as the economy is moving according to the logic of capital: industrializing, mechanizing, rationalizing. At some point, capitalism reaches its limits, and it cannot industrialize any further without destroying the social reproduction of the capitalists, this is the fetters of production Marx describes, after which the capitalist class becomes smaller and smaller until it disappears. The point at which capitalism hit these limits was 1979, and to overcome them, it has sacrificed the logic of capital, as well as the working class, to preserve the capitalist class.

In previous blog posts I’ve discussed how my simulations reveal the equalization of depreciation and investment whenever the rate of exploitation and rate of capitalist consumption stop moving. You can play around with one of these simulations here, which also shows the dynamic conditions where changes in the rate of exploitation and rate of capitalist consumption cancel out changes to investment. We happen to be living in a historical moment where a rising rate of exploitation and capitalist consumption somewhat cancel out any effect on investment. However, if we were to reverse this, and hit the limits that we did in the 70’s, the only way to increase investment further would be the destruction of the capitalist class.

The point is these variables are socially and politically determined. Today, the increasing consumption of the capitalist class stand in the way of further investment and improvement of material infrastructure, not to mention the living standards of the working class. Declining investment has led to an increasing convergence of investment and depreciation. It’s this lack of investment which I believe is responsible for increasing stagnation of labor productivity, particularly in manufacturing.

Of course, one day, regardless of what we’ll do, we’ll hit the limits of what investing additional social resources to infrastructure will do for us, and the only material improvements will come from the application of new scientific discoveries. The question is, how do we get there? How do we get past the wall of capitalist social reproduction?

The only way, in my opinion, is through a mass understanding of crisis theory and national accounting. In the 70s, people may have grasped that the attack on the working class was the only way for capitalism to persist, but they didn’t grasp its opposite, that the only way for the working class to keep its gains, as well as continue economic rationalization, was to destroy capitalism. Grossman’s politics were essentially correct and, as his recent biography goes to show, not reducible to a kind of empty economic determinism about the inevitability of socialism. They were a strategy for taking advantage of a crisis, to allow people to understand what they meant. While every political crisis might have specific political sparks, such as the start or end of a war, what has caused structural shifts in the global economy has always been crises.

The covid crisis has caused such a shift, and we’re starting to see evidence that states are forcing higher levels of investment. If this continues, we may find ourselves back in a 1970s style profitability crisis once more. It would be better if we could be prepared to see the limits of capitalist reforms in such a situation.

See “The End of Capitalism: The Thought of Henryk Grossman” by Ted Reese.

I have taken your recommendation and tried doing the rate of profit for british columbia using consumption of fixed capital (CFC) instead of using the capital stock. It doesn't actually look that different from stock-based measures, but I like this way better because it avoids the problem of having to "switch horses" or use Perpetual Inventory Method (PIM) to backwards estimate the capital stock. Instead, I just backcasted by chain-linking the pre-1981 growth rates to the 1981 base year. This allowed me to keep two series continuous. Thanks for the inspiration!

do you have this published "academically/officially"? i'm trying to do my undergrad thesis on the trpf, and i'd like to include this in my rrl