At the end of a political economy piece I published in September 2023, I noted that the long legacy of under-investment caused by neoliberalism seemed to be ending due to the Covid Crisis and a new tendency of state-led investment1. If this tendency of higher investment persisted, I predicted it could lead to a new profitability crisis. But instead, it seems that this investment push has highlighted an even deeper crisis in the American economy, and one which is at the root of the current attack on the Federal Government by the high bourgeoisie. This crisis is precisely the sort experienced by the late Soviet Union, an inability to actually utilize the resources marshalled by investment, and therefore a breakdown in the production of use values. Unlike the Soviet Union, where the state socialist system had limited access to world markets and goods were rationed broadly, this breakdown in production of use values is not experienced as shortages but higher prices and loss of market share.

My previous work on investment in the US economy has highlighted just how investment stagnated in the neoliberal period. The point of this blog is to show how this underinvestment, combined with Chinese competition, bureaucratic red tape and social atomization, have led to a breakdown in the technical-scientific environment and incentives broadly necessary for efficient industrial production.

What was neoliberalism?

Neoliberalism was an attempt by the capitalist class to forestall the existential threat to its reproduction by state capitalism and falling profit rates, which in the 1970s and early 80s, led to a crisis of profitability that mobilized the class politically. The Kalecki profit equations show that profits are equal to investment plus capitalist consumption, and therefore also show how investment is directly in conflict with capitalist consumption. My profit rate computer simulations, based on the Kalecki equations, expand on this by using the rate of capitalist consumption (the inverse of the investment rate) and the rate of exploitation, to show what dynamics are behind the tendency for the rate of profit to fall as Marx identifies it. Marx believed that increasing competition would force investment in labor saving technologies, and therefore, constant capital would increase in proportion to variable capital (wages) and surplus. In order for this to be true, my models showed that investment would also have to be an increasing share of total value, which was precisely the case on all historical records up until the neoliberal period. The “social democratic” or state capitalist period of development from the 1930s to 70s also combined this rising investment rate with a falling rate of exploitation, which doubly decreased profit rates.

After the 1970s, however, capitalist consumption as a share of surplus (pictured below) ceased to fall, and thus investment as a share of surplus ceased to increase, and indeed this tendency started to reverse itself somewhat. We’re all familiar with the stories that accompanied this transformation, companies were cannibalized by private equity, production was sent overseas, or foreign competition prevailed over domestic producers.

This situation has been especially severe for American manufacturing. Real investment in manufacturing was basically stagnant between 1979 and 2009.

But this didn’t necessarily mean that industrial manufacturing output was stagnant during this time. Industrial output kept going up, as well as labor productivity, until 2008.

What is remarkable is that even as investment in U.S. manufacturing has skyrocketed the past five years, this trend has not reversed. This investment was supposed to spur growth and greater production of industrial goods. But none of that materialized. My original point had been premised on that hypothetical growth, but its absence is actually a much larger problem.

What caused the decline of productivity in U.S. manufacturing?

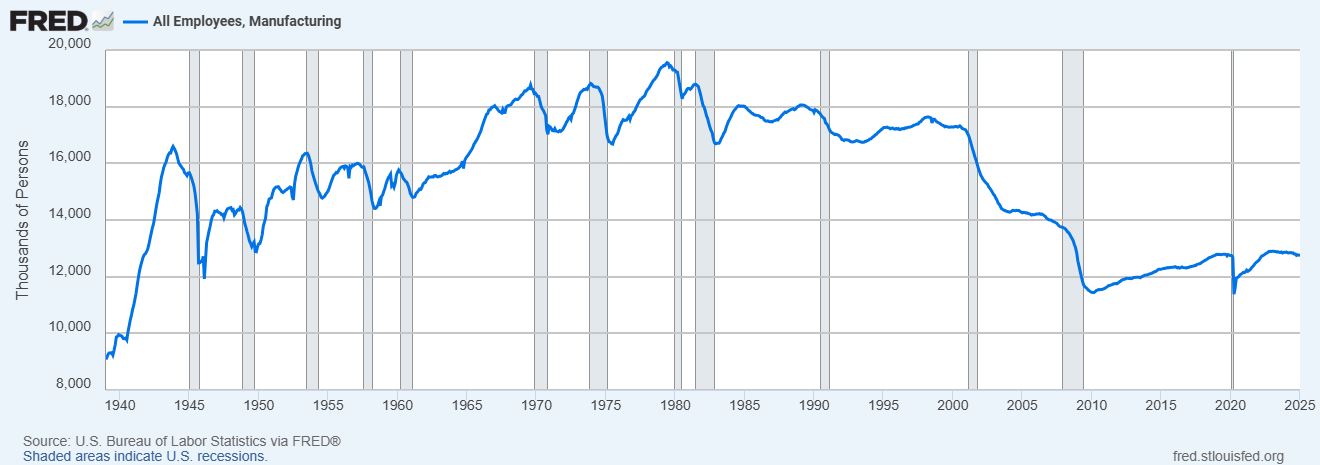

The early, pre-08 neoliberal period was marked by increasing productivity of both labor and capital in industry, which allowed manufacturing to make the most of less investment and laborers. It’s worth noting that U.S. manufacturing employment didn’t actually begin falling precipitously until after NAFTA and China’s entry to the WTO in 2001. 2008 was just about as big of a collapse in manufacturing employment as the China shock.

Things begin to get interesting once we compare this graph, of manufacturing employees, to the investment rate (fixed investment share of surplus) in the post-war period.

Between 1946 and 1979, the number of manufacturing employees mirrored the investment rate closely, and the two were still somewhat correlated after 1979, but they also began to significantly diverge. Mostly this is due to manufacturing becoming a much smaller share of the economy, if we look at specifically manufacturing investment as a share of surplus, it’s much closer to the line for manufacturing employees.

Here it's clear that American manufacturing tread water between 1983 and 2000, and then experienced two phases of collapse in the 2000s and post 08 economy. What’s remarkable is that the past five years have not made this investment rate for manufacturing turn around, despite the supposed jump in inflation adjusted manufacturing investment in this time. Even as inflation was rising during this period, profits were rising faster, and basically made the state-led investment become a wash, leading to the post-08 equilibrium to be reinforced rather than escaped.

It may be argued that the Biden administration has succeeded in these investments, after all, there are real investments in chip manufacturing which are starting to bear fruit. The TSMC fabs in Arizona appear to be just as productive as the ones in Taiwan. But this is also a reflection of existing trends. Even as US manufacturing has collapsed as a whole, manufacturing of computer parts like chips has continued to trend upwards.

As the Biden era industrial policy has shown, this is a sector of immense strategic importance, and which will probably continue to receive investment and attention. But the statistics are clear that investment in manufacturing, along with employment in manufacturing, has basically collapsed in the US outside of this sector.

It’s my contention that this collapse in both investment and manpower is not primarily the result of productivity gains which have magically made the costs of machinery or manpower much much cheaper. This drain in investment and man-power has also probably led to brain drain, as the people with manufacturing know-how retire or die. Perhaps in the 80s and 90s the US could still rely on the same people with manufacturing experience and expertise as they had in the 70s, but no more.

In the late 19th century and early 20th, the US was known less for its ability to make theoretical innovations than its ability to put these theories into practice. The US was the center of applied science, and Europe the center of theoretical science. Now, 100 odd years later, the situation has changed. China is now known as the center for applied science and the US the center of theoretical science2. Several, quite intelligent, people I’ve spoken to suggest that this US innovation will continue to preserve the American edge vs China. But history seems to suggest otherwise.

A 2023 American Affairs article pointed out that the American manufacturing innovation system has been lagging international competitors since the 1970s. The post-war innovation system was designed in such a way that the government and universities would handle basic research, and make this research available to companies for implementation. This innovation pipeline broke down in late-fordism due to companies and managers being set in their ways, not particularly looking at how to streamline or improve the manufacturing process itself except when made absolutely necessary by competition. Then this pipeline summarily collapsed under neoliberalism. Now, the problem was not just stubborn companies and managers, but it was the total lack of willingness to invest in production at all. Manufacturing was moved overseas where cheap labor substituted for labor saving technologies. Manufacturing in the US was moved to low-unionized areas to similar effect.

The manufacturing that remains in the US is atomized, both physically and to a lesser extent socially. Large factories in the outskirts of upstate New York or Texas cities where real estate is relatively cheaper, remains isolated from centers of technical innovation. Companies may sometimes have contacts in academia with specialized experts, probably a thousand miles away, but there is no system for integrating innovation with iterative improvement of the manufacturing process. Contrast this to China where universities are tightly integrated into massive industrial parks, and where co/byproduction in chemicals, minerals and manufacturing is the norm, coordinated by local governments and state enterprises. Inventors and startups have easy access to every type of mechanical and electronic parts, and can typically iterate in a matter of days what takes in the US weeks or months. Ostensibly, the US has laws which incentivize universities to commercialize innovation, but this is in the typical atomistic way of our type of capitalism, without consideration for what other systems, companies, and products may be synergistic with these innovations.

But the problems facing the US economy are not just purely of this collapse of manufacturing. In many areas, the legal-regulatory system of the US has caused the cost of many basic things, particularly housing, to explode. Real investment in housing has risen even as the number of housing starts has roughly continued at historical averages.

Indeed, we can compare the real dollars spent on manufacturing, and housing versus the actual use values they produce. See the graph below, which calculates this as a ratio for each, housing in the blue line, manufacturing in the green dotted line.

In the case of both housing and manufacturing, the current output per real dollar invested is roughly half what it was at its peak. The peak being the 1960s for housing, and the early 2000s for manufacturing. This is frankly an incredibly bleak trend for two of the most important categories of goods in a capitalist economy. Assuming that the CPI adjustment is adjusting these investment levels for the changes in the general price level, this means that more and more real resources are being invested into these sectors with less and less to show for it. It is, what we might term, a collapse in the productivity of capital. That is, at least, one interpretation of events.

The other interpretation is that the prices for investment goods and capitalist consumption goods have risen faster than ordinary consumption good prices due to the effects of monetary overaccumulation. We can find out more if we look at price indexes for industrial means of production vs housing.

In this case, it appears to be a bit of both. Housing prices in particular have skyrocketed, whereas machinery prices look practically like a steal in comparison. What’s happened is a curious combination of several dynamics at once. If the housing supply hadn’t been constrained, it wouldn’t have been such a target of the over accumulated funds in the hands of the bourgeoisie. The permitting and zoning process are real obstacles to building that have effectively constrained supply, and increased costs both in a technical way (more paperwork) and through attracting investors to what are reliably rising asset prices. After all, investors always do supply and demand analysis, extrapolating from construction trends, to do the underwriting for real estate investment. This doesn’t necessarily mean that reforms to zoning and permitting are the magic bullet YIMBY activists think they are, a market driven approach wouldn’t necessarily lead to generally lower prices unless capitalists are actively making big mistakes in underwriting.

With regards to manufacturing, how can it be that real costs have risen so much for such little change in output? The shift away from traditional manufacturing, to computer manufacturing explains some of this, as it requires extremely expensive machinery unlike most other manufacturing industries. The rest, I believe, is explained by the dynamics I’ve described above. The bourgeoisie effectively allowed the american manufacturing system to atrophy, losing institutional knowledge and “human capital”, and is now left with an atomized system of production and scientific knowledge creation no longer capable of effectively coordinating among itself to achieve real manufacturing innovation.

The Ideological Origins of the Present American State

Now, the present administration, of Donald Trump and Elon Musk, is notably not adopting many of the recommendations of that 2023 American Affairs piece, written, perhaps, during the high period of 21st century American industrial policy. Instead of pushing for new industrial policy programs, they’re busy trying to cancel the old ones. The new tariffs aren’t targeted to revive US industry, they will just as well hit inputs that manufacturers need, therefore making US manufacturers voluntarily pay higher prices and have higher costs than the rest of the world. Indeed, even Trump’s inaugural speech seemed more focused on oil and other natural resource extraction than manufacturing. The attack on federal bureaucracy has equally been scattershot, shutting down the CFPB and USAID, agencies which were the locus of a few high bourgeois and far right grudges, respectively, but which will likely do little to strengthen the American industrial base. What’s behind the ideology motivating these moves?

My contention is that it is what Althusser would have called a sensuous, empiricist, and historicist ideology, and that it is an ideology uniquely born of an encounter between the high bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie. In these facts, it is similar to fascism in form, although less so in content, due to important differences in the material conditions between the present day and the 1930s.

The Sensuous Reality of the American Bourgeoisie

Althusser criticized the early Marx, as well as other Marxists like Gramsci, for an emphasis on the sensuous and empiricist origins of truth. This sensuous empiricism gives epistemic primacy to things we can directly feel and experience. Intellectually, this point of view has an ideological “lineage” through thinkers such as Gramsci and Luckacs into modern feminist stand-point epistemology which experienced periodic resurgences in academia since the 1970s. The point of Althusser’s critique was not just that this epistemology was “subjectivist”, but that it deliberately constrained the type of knowledge that we could create. If everything is as it appears, then it means that the true meaning of things is already there, ready and at hand, in the things we encounter. It constrains our ability to learn, to apply broader systems and operations of thought, abstractions, to our particular situation and figure out what exactly is going on. In Gramsci, the particular sensuous, empirical phenomena which was the subject of his theory was the political, and thus theory was subordinated to “what worked” politically. Althusser called this particular type of ideology historicism, because it subordinated theory and praxis to what was politically expedient in a particular historical moment.

But we shouldn’t just assume that this sort of ideology only exists on the left, although, the forms on the left tend to be more explicit about this sort of operation. Francis Fukuyama and Samuel Huntington can be thought of as bourgeois historicist ideologicians. But even that type of theory is too sophisticated to describe the current regime. What else is the “common sense” that Donald Trump has repeatedly cited but a defense based on the epistemic certainty of the sensuous reality.

When asked why he was so certain DEI was behind the recent Ronald Reagen airport plane/helicopter collision, Trump said the following:

Q: “I understand that. That’s why I’m trying to figure out how you can come to the conclusion right now that diversity had something to do with this crash.”

TRUMP: “Because I have common sense. OK? And unfortunately, a lot of people don’t….”3

Trump also cited a “revolution of common sense” at his inauguration.4 Conservatives have further lauded the Trump and Musk administration for its ability to “move fast and break things”, suggesting that this may be a sign of a final break from the long 20th century which was characterized by timidity in the face of strong principles and sentiments, afraid to repeat the horrors of the 2nd World War caused by ideological certainty. The truth, however, is that “move fast and break things” is not at all alien to the 20th century, nor does it seem that there is anything beyond the mere appearance of strongly held masculine values, as the right would have it. The Iraq wars, the Russian shock therapy, are some incredibly recent instances of this self-confident US empire. As one Bush aide put it at the time:

The aide said that guys like me were "in what we call the reality-based community," which he defined as people who "believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality." I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. "That's not the way the world really works anymore," he continued. "We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality -- judiciously, as you will -- we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do."5

The lack of self confidence felt in the atmosphere by the right is really only a phenomena after the apparent failure of the Bush’ empire-building project, which, for sure, has been 20 years by now. How time flies.

All of which is to say, this right wing enthusiasm is very much “vibes based”, and subordinated to political expediency which has no deeper theory behind it. There is little real substance to it besides the contradictory semiotic field of ideology created by right wing media, which explicitly works to identify DEI, the CFPB, foreign aid, and Marxist government bureaucrats as the chief causes of American decline. But it is important to note that this operation would not be possible if it was only media ideology production. The bourgeoisie, both high and petty, experienced this collapse of the production of use values, just as well as anyone else. And their class position caused them to experience it in a particular way, as well.

For the bourgeoisie, who live off a given accumulation of money capital, the issue of use values is actually an extremely important one, just as much as profit rates. This is because, except for those who have enough money that they can live off very basic financial returns, the bourgeoisie must buy factors of production in order to play their role in the circulation of money and commodities, just as well the commodities they use to physically reproduce themselves, like housing, food, clothes, ect. If, in the case of real estate, the price is extremely high, this limits the amount of people who can become bourgeoisie because this factor of production, (land, buildings) is out of reach, as well as limit the returns of those who use the land and buildings as a factor of production. Complaints about the permitting process for industrial production, energy production, and all kinds of such activities abound.

These sort of issues also apply to situations where use values are scarce for non price related reasons. This is the issue with US manufacturing. American manufacturers can buy all the same machinery as anyone else can from Germany or China, but what we lack is an innovation and manufacturing ecosystem which can keep American manufacturing competitive. For the industrial bourgeoisie, which includes people like Elon Musk, this appears as unfair competition from abroad. Of course, Musk, and most of the American high bourgeoisie, have too many business interests in China to make this into too large of an issue. It’s notable that Trump 2.0 is much less aggressive on China than Trump 1.0, likely due to this way the high bourgeoisie has joined his coalition. Nonetheless, the mercantilist edge persists, an outgrowth of these direct economic interests but not understood much deeper than this sensuous sense that “foreign competition has been bad for America”.

The sensuousness of the intellect behind the Trump Musk administration also directly prescribes its limits. Any actions which threaten to significantly undermine financial markets are unlikely. The various feedback loops which form the most basic interests of the bourgeoisie continue to discipline the administration in this sensuous way, through flashing numbers on the TV. But, of course, these limits could still be exceeded without knowing, on accident. That too, however, is more a limitation than a true evolutionary spandrel, for the exact way the process fails is unpredictable. It is unlikely, however, to produce a popular or enduring shift, rather the opposite, more likely to generate an intense backlash. Already, the administration and its partisans seem unaware the extent to which its policy disruptions appear to benefit a small clique of insiders and oligarchs, or rather, unaware of the extent to which others are aware.

That’s not to say, there are no rational kernels to this ideology. The attack on government bureaucracy is symptomatic of the simple fact that such bureaucracy built on top of educated professionals is 1) expensive, and 2) disconnected ideologically from all non professionals. However, as Samuel Huntington pointed out with regards to the professional military officer corps, which is also formed by ideological discipline within liberal education, reducing the autonomy of professionals also reduces their effectiveness6. Rule and ideological discipline by a small clique, the tendency of all Bonapartist regimes, can solve the immediate problems, but is less stable in the long term.

What I have great certainty in, despite all the vicissitudes of the current historical moment, is that the Trump Musk regime will not be capable of creating a new system “that works”. Its ideology can not reverse the decline of American industry, and it appears very close in its actions to implicitly acknowledging the accomplished fact of this decline, in the transformation of the American economy into a purely extractive enterprise.

The Real Contradictions

This blog began by acknowledging where I had gone wrong in my estimating of where Biden era industrial policy was going. I had been worried that those who dismissed the falling rate of profit as a real contradiction would repeat the mistakes of the past. That is still possible, however, the present economic contradictions are even more severe and immediate than the possibility of a profitability crisis. Although, for sure, a profitability crisis would make things much worse if it were to occur.

The contradictions are more fundamentally the ability for American capitalism to produce key use values, for it to transform monetary investment into actual factors of production. The Biden administration was already failing to simply send checks out in the mail, much less actually revitalize American industry. The Trump Musk administration, similarly, only has the ambition to destroy, rather than create anything new.

The startling truth is that the problem can no longer be fixed by simply throwing more money at it. The people who could have used that money in American industry are mostly gone. Nor can it be solved by simply firing federal workers or defunding NGOs. Most of the largess of educated professionals isn’t in Washington or on the Federal Payroll. The American ruling class is in the process of realizing that the easy solutions it thought it had have quickly slipped through its fingers like smoke. As US companies lose global market share to Chinese capital, this problem will become increasingly acute, as suddenly the largess, of both the professionals and the petty bourg, can no longer be sustained through access to cheap foreign labor. From this perspective, absent radical alternatives, the future appears like Argentina, stabilization at the cost of rapid impoverishment of the population.

“The covid crisis has caused such a shift, and we’re starting to see evidence that states are forcing higher levels of investment. If this continues, we may find ourselves back in a 1970s style profitability crisis once more. It would be better if we could be prepared to see the limits of capitalist reforms in such a situation.” https://nicolasdvillarreal.substack.com/p/the-tendency-for-the-rate-of-profit

Levine, Emily J. 2021. Allies and Rivals : German-American Exchange and the Rise of the Modern Research University. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. “Germans like Klein were self-assured about their palace in pure science but argued that Germany must emulate America in applying that science for Germany’s advancement. Americans like Gilman, in contrast, thought what America needed was a pure research institution…”

Huntington, Samuel P. 1964. The Soldier and the State. Vintage.

Contrast this to China where universities are tightly integrated into massive industrial parks, and where co/byproduction in chemicals, minerals and manufacturing is the norm, coordinated by local governments and state enterprises.

I was a process scientist at the legacy Upjohn (now Pfizer) API manufacturing facility in Kalamazoo MI. Out labs were right on site. I could leave my office and be on the plant floor in 2 minutes. When I and any of the other scientists had a process we were developing/transferring in from another site we would have the equipment we planned to run it in mind as we developed since we were all familiar with the plant. The result was we never turned anything down and got everything to work and that kept Pfizer from closing us down, even though they did not like the way we did things--having all the R&D support right at the plant, responsive to the plant's needs--rather than in a central location supporting multiple smaller plants in their network.

That the Chinese do it our way makes sense.

What is the 'real contraction'? To me what is going on looks like a split within the capitalist class as capitalists operating on the national market are out-competed by global operators. The neo-liberal framework was put in place to benefit the globalists. The nationalists now struggle to pull this framework down even if they do not have any clear concept of what is to follow.