Over the past year, as the federal reserve has rapidly increased interest rates, something extraordinary has happened: Federal Reserve banks have been losing money, slipping into negative profitability for the first time on record.

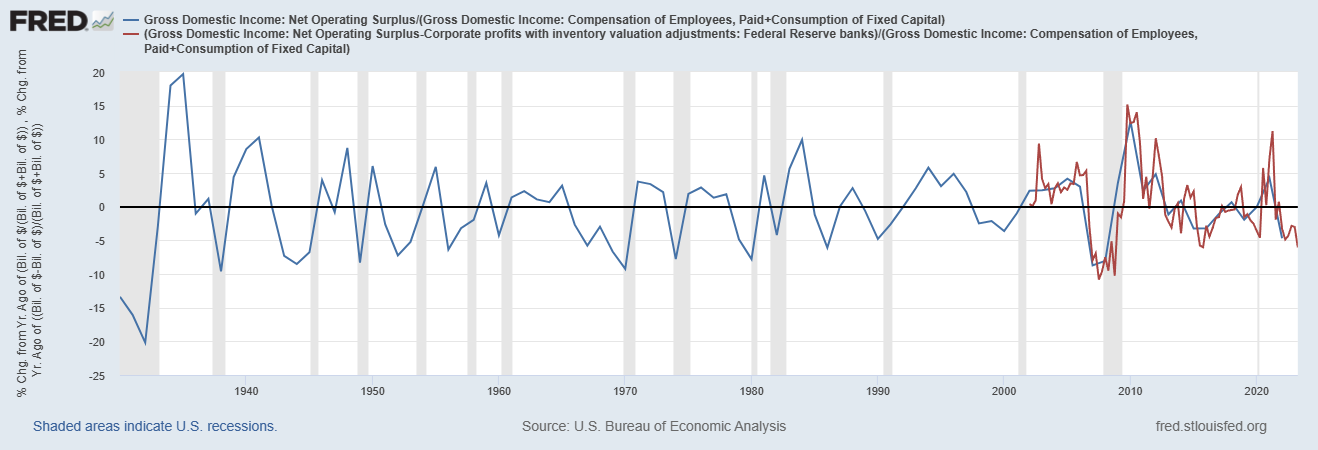

I first discovered this when I recently checked in on rate of profit stats for the country, which I do periodically, and saw an astonishing anomaly.

When we look at this data as a year over year change, this dramatic drop in profitability is on par with the global financial crisis, the Volcker shock and the great depression.

I quickly discovered that the sudden and intense losses on the Federal Feserve income statement were the cause of this anomaly. Incidentally, I also found out that federal reserve banks are technically counted as private businesses in national accounts, which is funny in a cosmic irony sort of way. See, the Federal Reserve doesn’t have the same kind of budget restraints as other businesses, or any kind of institution more generally, even less restraints than the federal government where spending is a fundamentally political decision. When the Fed loses money, it can simply write an IOU to itself, which resolves when it makes a profit later1. This means that the significance of this rate of profit signal is not what it would ordinarily seem - if this drop was caused by actual private businesses, we would be seeing cascading business failures across the country. If we adjust for the Federal Reserve by removing its profits from the equation we get a graph which is much more in line with a regular business cycle, albeit one that is primed for a modest recession.

This isn’t to say the lack of profitability at fed banks is totally without consequence; so long as the fed has IOUs it can no longer post dividends to the treasury, which are not an insignificant amount: 137 billion in Q1 2022 for example.

2023 marks the first year that the Fed has posted zero dividends to the treasury since 1946. Considering that the largest source of federal reserve income is from US government debt payments, this is mostly just the Fed sending the treasury money it itself sent it, reducing for the cost of its operations. More recently, with the rise of quantitative easing in the 2010s, the Fed also began to buy mortgage backed securities in order to provide more liquidity to financial markets, and these kind of securities are its second largest source of income2. See the excerpt of the most recent fed financial statement below.

You might also notice, in this same excerpt, the extreme change between the first six months of 2023 and 2022, the sudden increase in interest expenses.

The Fed basically went from making $69 billion in net interest income to negative $53 billion in one year. This is the result of their rapid interest rate increases over this period, as well as the post 08 monetary policy framework, hence why this negative profitability is so new.

It used to be that the Fed would primarily exchange Treasury securities (T-bills, bonds, ect) with banks in order to adjust their reserves, with higher levels of reserves associated with lower discount rates from banks and vice versa. Banks did not earn interest on required reserves, thus, in a world with inflation, holding reserves was always a cost to the bank and they only ever held slightly more than what was required by regulators and to meet demand for customer withdraws. In this world, the interest rate of last resort was the one created by the market for lending excess reserve between banks, this was called the federal funds market, and the interest rate in this market, the federal funds rate, is what the Fed would target with its monetary policy, intervening in this market by buying and selling Treasuries to get the interest rate where it wanted. This interest rate essentially represented the risk-free return for a bank’s money, and thus the floor for almost all other interest rates in the economy.

The 2008 crash forced major changes to this framework. Policymakers wanted banks to carry more reserves in order to prevent embarrassing and destructive collapses. One thing they did was mandate higher capital requirements, but another thing they did, which is more relevant now, is having the Fed start paying interest on required reserves. These required reserves are held at Federal Reserve Banks, which made this new interest rate paid by the Fed the new risk free interest rate, and the floor of interest rates in the financial system3. It also, simultaneously, introduced a new expense category for Federal Reserve Banks on its income statement, which today is the biggest driver of its unprofitability.

But interest on deposits wasn’t the only big change - another result of the financial crisis was an increased role of repurchase agreements for monetary policy. Repurchase agreements are essentially a type of collateralized loan, the Federal Reserve sells a security to a bank and then buys it back at an agreed upon price. The difference between the two prices is essentially the interest earned on the loan. When interest rates are higher, as they are now, the Fed is making repurchase agreements that have higher price differentials, thus generating higher returns for the banks they’re making the agreements with4. The end result is another kind of risk free rate for banks the Fed can manipulate, as well as another interest expense for the Fed. While the Fed did repurchase agreements before 08, they became much more prominent afterwards, especially after 2013.

Up until now, much of the emphasis of monetary policy has been on the Fed’s balance sheet, and its effect on other bank balance sheets. In the old framework the Fed was buying and selling risk free assets, Treasury bonds, and for much of the 2010s, when so much of monetary policy was focused on preserving market liquidity, e.g. quantitative easing, these same kinds of purchases continued. Over the past year, as we’ve experienced rapid monetary policy tightening, the full consequences of the new framework have become apparent. The new framework is a framework of monetary policy through the income statement, rather than the balance sheet.

For non-accountants, let me explain what this means. Everyone out there who makes and spends money has both a balance sheet and an income statement. Your balance sheet contains your assets and liabilities, all the stuff you own and all the stuff you owe others. Your income statement, in comparison, contains the records of your income and your expenses. For a long time, especially when interest rates were close to zero, people often talked about how companies and individuals could do spending by leveraging their balance sheet instead of getting higher income. When you take out a loan, both your assets and liabilities grow, you get both cash and an IOU saying you owe that cash back plus interest. The real cost of that loan is the interest you pay, and that shows up on your income statement as an expense along with whatever you spend the cash you got from the loan. So long as you can pay interest expenses, and people are willing to loan to you, you can make expenses far in excess of your income.

But income still matters, indeed it can matter a great deal. Loans, and most financial instruments, from the buyers point of view, are ways to buy access to an income stream. Even collateralized loans require an expected stream of cash which can be used for repayment. For companies, and the individuals who rely on them for some kind of owner disbursement, it is net income, profit, which is what counts. As I’ve explained many times previously, the capitalist class needs profit in order to reproduce itself, it needs companies to maintain a net operating surplus, as well as profits after taxes and other extra costs. If they don’t have profitability, they’re essentially cannibalizing the company and losing their method of reproducing their class position. You need profits in order to regularly make dividend payments, owner withdrawals, or share buybacks.

When I say that the Fed has shifted its monetary policy framework from a balance sheet framework to an income statement one, this applies not just to the Fed’s own income statement, but also to the income statement of the banks it exercises monetary policy through. It used to be that banks would primarily exchange a financial instrument, a promise of future income and cashflow, for present day cash, or vice versa, with the Fed as a part of its exercise of monetary policy: changing the composition of its balance sheet. While it’s possible some profit was made via these exchanges, there existed a fair market value for these assets (Treasuries), and this market was usually extremely liquid; it is notoriously difficult to make money purely from buying low and selling high. The real source of income for the banks on these operations came from the interest paid on the Treasury bonds themselves - the source of income being the Treasury and the Federal Government. The new monetary policy framework since 08 has changed this, the Federal Reserve is now the source of interest paid, specifically on deposits held at Federal Reserve Banks and with the “interest” paid on Fed repurchase agreements. And the loss for the Fed is the gain for the big banks.

The Bailout

With both the bank bailouts and quantitative easing, there were promises of how the banks would be paying back the government, and by extension the American people. The banks got their liquidity, but in exchange the Fed got bonds or other kinds of IOUs. Indeed, this arrangement was very profitable for the Fed if we reflect back on the first graph of this blog. But I don’t think people took the time to think about that promise too hard. If it’s possible for the Fed and the government to make profit from the finance industry, wouldn’t it be possible for the opposite to happen as well? Fundamentally, all that prevented it was the extremely low interest rate environment.

I suggest we take the advice of the BEA and consider the Fed as a private business for a moment. Throughout the 2010s it generated roughly 20% of all profit in the US finance industry5. Notably, this profitably decreased during the interest rate tightening period of 2017-19. The income, as mentioned before, was coming from Treasuries and Mortgage Backed Securities, and the expenses were extremely low since the interest the Fed had to pay to banks was almost nothing. So long as interest rates were low, the Fed’s framework actually hadn’t changed much - they didn’t pay interest on deposits before either. Higher rates radically changed its business model, however. Suddenly all the income it received from Treasuries and other securities was overshadowed by how much it needed to pay on its deposits and repurchase agreements.

This expense naturally becomes income for the banks on the other side of these transactions. Now, banks usually do make money off interest rate tightening cycles. The increase in the interest rates on bank deposits for their customers lags behind the increase in rates on loans and bonds and other financial instruments. Certainly, if you look at bank income statements you’ll find an increase in both interest income and expense, and increasing interest income from industrial loans in particular when we restrict ourselves to private industry sources. What is extraordinary, however, is the sudden expansion of its interest income coming from bank deposits held by the bank and resale agreements.

For the 7 big American banks I looked at, the share of interest income coming from the Fed jumped threefold compared to the same period last year. When we aggregate data from all 7 banks, it went from 6% in 2022 to 25% in 2023.

When we look at the income attributed to the Fed as a share of the total revenue for these companies, it’s even more astounding, going up by an almost order of magnitude: from 3% to 27% overall, and with some banks seeing it rise to over 50%. Now, partly this is because companies only count net interest income in total revenue, thus including interest expense. But this metric is still important because it allows us to start thinking - what would happen if this income stream didn’t exist, as it hadn’t existed for most of history.

When we subtract the new estimated income attributable to the Fed, and hold it at 2022 levels, this is what bank profits start to look like. Many banks are no longer profitable at all, and, when aggregated, big banks are making a measly 2% profit rate, largely propped up by JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo. Without the income from the Fed, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and New York Mellon would be losing money hand over fist.

While the Fed has been forced to pause dividend payments to the Treasury, banks that would otherwise be unprofitable without direct income from the Fed have continued to make dividends and share buybacks, even increase them. In Q3 alone these banks, whose profitability has been assured by the Fed, sent $4.6 Billion back to shareholders.

Unlike previous bailouts there are no strings attached, and unlike QE, where the fig-leaf of buying on an open market disguised how rising financial asset prices ultimately benefited financial capitalists, this is money going straight, directly, to banks and boosting their bottom lines, increasing their profits right there in their income statements.

Without this extra income to banks, however, credit conditions could have been much worse and the contagion from bank failures earlier this year could have been far more widespread. To the Fed, everything is going according to plan, this is how their new monetary policy is supposed to work. The fact that it's a massive, unprecedented giveaway to big banks might not have been anticipated by policymakers back when the post 08 reforms were made, but that doesn’t really bother the Fed, or the Biden administration for that matter.

In a previous blog, I wrote about how the Fed and financial markets which are used to set the interest rate represent the height of collective bourgeoisie power, and this is just as apparent here, in this most recent example of US monetary policy where interest rate hikes are currently being used to undermine tight labor markets and slow inflation. However, what these dynamics highlight is that our system doesn’t simply act to preserve existing bourgeois society and its institutions in the abstract, it also does so through the enrichment of a particular section of the financial bourgeoisie. The shareholders of these particular banks, through an ordinary utilization of Fed monetary tools, are making billions. Public policy, but always someone’s personal, private enrichment.

I put this blog together because this wasn’t something that seemed to be on anyone’s radar. Which seems strange considering how much controversy the original bank bailouts and QE generated. I believe this is partly because both of those policies were announced as changes in the status quo, but the policy change causing this current bailout, and it is, essentially, a bailout, were made over a decade ago. Much of the coverage about the Fed’s losses have focused on its impact on the treasury, who have lost the dividend income, or on the more generic benefactors of higher interest rates. Not many people seem to have made the connection between the Fed’s losses and the profits at big banks. Hopefully that will change, this isn’t the sort of thing that should go unquestioned. People should ask themselves, why does it have to be this way? Why do we have to abide by paying these people off in order to do basic functions of a central bank? If the only reason these banks continue to exist is income from the Fed, why shouldn’t they simply be expropriated?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?graph_id=1249103

Good afternoon Nicolas.

Yesterday was my first time being introduced to your work after reading through your Twitter discussion/argument with Jehu, and your work is very compelling so far.

However, I'm struggling to see how an increase in SNLT per commodity could be occurring if bailouts such as this are relatively new. And why is it that, since 2022, prices and M2 have decreased ever since this bailout? Shouldn't one expect the mass of money to increase?

Thanks in advance.