Financial capital is a spectacular thing, in the most literal sense. The financial press, 24/7 finance news, the incredible opulence and respect afforded to big financial investors, are proof enough of this. There are fabulous sums involved, trillions and trillions of dollars of financial instruments like derivatives, stocks and bonds. It cannot be denied that finance defines the interests and outlook of the bourgeois as individuals, and so it has become increasingly fashionable since the 1980s, and especially since 2008, to suggest that the logic of finance, that is the logic of capitalization, is what defines and structures capitalist society as a religious doctrine given life.

This is the theory presented by economists/political scientists such as Shimshon Bichler, Jonathan Nitzan and Blair Fix which has been called “Capital as Power” or CasP for short. Declaring that both neoclassical and Marxian political economy have been done in by their subscription to the idea that there is a real economy which regulates the nominal/financial economy, and that this real economy can be quantified, with utils and demand curves in the case of neoclassical econ, and socially necessary labor time in the case of Marxian econ. The CasP theorists suggest that these measures of the real economy are in fact unquantifiable, and that, in fact, there is no underlying real economy, that it is finance and finance alone which structures our social reality. In their own words:

“All capital is finance and only finance, and it exists as finance because accumulation represents not the material amalgamation of utility or labor, but the creordering of power.”

This is, fundamentally, a theory of extreme political determinism, though much of this exercise of political power doesn’t occur in the state, but through capitalist decision making in an economic sense.

The account within CasP of Marx and Marxian economics is quite poor, regardless of any comments about the failure of the labor theory of value, which also miss the mark. Many of the things they claim as unique insights, such as that the economy is not external to society but is in fact constituted by it, or that the rise of large hierarchical institutions would lead to the demise of the economy as a sphere of atomistic actors, were in fact already established by Marx in Capital volume 1. If you wish to read a more detailed defense of the labor theory of value, I’d suggest reading the book Classical Econophysics. But, rather than focusing on the textual analysis of CasP, I’d like to focus on the quantitative claims being made.

Their argument can be summarized as follows:

The accumulation of capital is a purely financial phenomena, totally detached from any physical assets like machines and factories.

Accordingly, accumulation is determined by the forward looking process/ritual of capitalization, rather than any backward looking process determined by objective measures

Through capitalization and other political measures, including decisions within firms, formal politics, and war, the capitalist class secures its place in society and its wealth

The chief example of using this power is through “strategic sabotage” where the capitalist class intentionally increases unemployment to increase profits

This argument is tied to several quantitative claims, a number of which are questionable. I will go through these questionable quantitative claims here:

Capitalization

First, to define capitalization. Capitalization is a method that capitalists use to arrive at prices for financial assets based on the projected cashflow. When I was working as a financial analyst underwriting real estate deals I had to become familiar with the practical application. The capitalization formula is given as follows:

K = E/r

Where:

K is the capitalized value/market price

E is earnings, the projected cashflow over a given future time period

r is the discount rate, which in most tellings relates to the time value of money

Capitalists, of course, don’t have a foolproof method for arriving at discount rates, so they just as well reverse this equation and test prices with a given income projection to see if they produce a respectable discount rate, such that:

r = E/K

It should be obvious that, in terms of determining a price, there is a large amount of circularity and overdetermination involved in this equation. Capitalists don’t have a crystal ball, they can’t know for sure what future cashflows will be, and a time value of money is inherently an arbitrary and subjective number to begin with. What they do have, however, are two ex ante metrics upon which capitalization can be based: the rate of interest, and the present day earnings on the asset. Capitalization underlies the distribution of capitalist income, which, while allowing for severe extremes in gains and losses, forces returns on financial assets to converge on a general rate that is difficult to outdo consistently, and which is totally detached from the profitability of the underlying assets.

However, even these meager statements about how capitalization works is a step too far for CasP theory. While Blair Fix admits the importance of present income as an ex ante basis for capitalization, he rejects the idea that interest rates determine discount rates. He cites as evidence this graph, which shows both discount rates at publicly trading companies and the effective federal funds rate, and focuses on the lack of a spike in discount rates during the interest rate hikes of the early 80s, especially compared to the early spike in discount rates in the mid 70s.

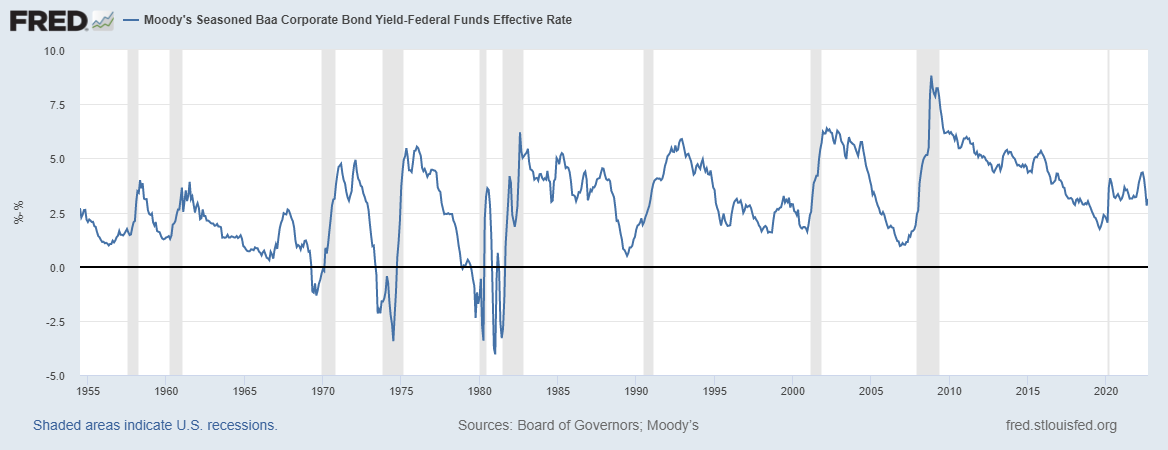

Fix makes a number of mistakes in this critique. For one, by using the Federal Funds rate he doesn’t use an interest rate that approximates discount rates. While the Fed Funds rate is the benchmark, its influence on other interest rates varies over time, as a policy variable it can be rapidly increased or decreased to force reactions from markets. This is particularly true in the 70s and 80s, when the Fed Funds rate was actually higher than corporate bond rates. See the graph below which subtracts the Fed Funds rate from the Baa corporate bond yield.

Using corporate bond interest rates would be a much better approximation. To see how well, we can divide profits by the corporate interest rate and then see how close it comes to market capitalization. Unfortunately, since I do not have access to the Compustat dataset, profits in my dataset are for all corporate businesses rather than simply publicly trading ones. But the results are revealing nonetheless.

Profits/BAA Corporate Interest Rates correlates extremely well with US Market Capitalization, which is what we should expect if interest rates are a large determinator of discount rates.

Compare this to using the effective funds rate.

Or Fix’s preferred driver of discount rates, the rate of inflation, which he suggests influences the perceived uncertainty of future income.

Why are interest rates so important to capitalization? It’s not simply that they stand in for a general measure of risk or the time value of money, especially given how they are influenced by benchmark policy variables, it’s that leverage, that is loaning money to finance the purchase of assets, is an important part of the process.

Say that you have a cash producing asset, and an investment bank decides they’re going to buy this asset completely with leverage with the understanding that the principal will be paid back when it’s sold after a certain amount of time. In order to make any money back on the asset, the cash payments from the asset must exceed the interest payments on the loan. This is also true from a comparative investment point of view, if the rate of interest is higher than the rate of return on other kinds of cashflows, including industrial profits, people will simply buy bonds instead of investing in those other cashflows. It also becomes uneconomical to take out loans to invest in production in such a situation, as doing so adds liabilities greater than the expected additional cashflow. If the general rate of interest is higher than the general rate of industrial profits or even approaches it, this can entail a massive disruption of production, as was the case in both the Great Depression and the Volcker Shock.

This general rule, of interest rates necessarily being lower than profit rates, was something pointed out by Marx in his comments on the rate of interest. It doesn’t apply directly to discount rates, as the price involved in capitalization is a purely financial phenomena not tied to any actual cost of production, but it is indirectly linked due to the influence interest rates have on discount rates.

Fix and the CasP theorists reject the idea that capitalization is mostly determined by backward looking information, instead pointing to the subjective factors among the capitalist class. In this sense they are methodologically similar to the Austrian economists who reject any quantitative measures of value while insisting on the importance of the collective desires and foresight of capitalists. The CasP position is particularly untenable for a very important epistemic reason. All knowledge about the future, all forward-looking projections, are necessarily contained in present information and created by people who can only remember the past. While the wild desires and fantasies of capitalists can create quite extraordinary capitalizations for certain companies and assets, all cashflow projections and discount rates must begin with present day earnings and interest rates.

If you look for it, you can find many problems with this collapse of the real/nominal combined with this forward-looking determination. For example, in firms capitalization of fixed capital investments produces a depreciation schedule which outlines the expected life of the fixed capital in question, such as machines or a structure. Over the productive life of the fixed capital depreciation will convert the value of the investment from an asset to a cost, with a total conversion complete when it is all used up. If a machine breaks down before the expected end of its useful life, or lasts far longer, the depreciation schedule must be adjusted on the basis of this backward looking record.

The real world once again intrudes whenever we leave the realm of pure finance and enter the firm as it makes investment decisions on physical assets. Capitalization of stocks and bonds has little to nothing to do with real fixed investment except in the most extreme cases. While stock market bubbles can help spawn new industries and investment, such as the case with the Dot Com Bubble and the more recent Tech bubble by giving firms easy access to money through sky-high valuations, this is the exception, not the rule. The vast majority of fixed capital investment is done with retained earnings of firms. Rather than leading to real fixed investment equity usually exists to extract funds from firms instead.

Why is this fact important? After all, CasP theorists don’t seem to claim that financial investment has a 1:1 relationship with actual investment, in fact quite the opposite. It is important because it raises an important question, if finance is supposedly structuring our reality how exactly is it doing that if it isn’t actually structuring material production? The answer from the CasP theorists is twofold: accumulation of financial capital is the accumulation of power, the need to secure differential accumulation, between capitalists and between classes, leads to the exercise of power in the various ways mentioned before. Chief among them is through strategic sabotage, one of the key empirical insights of the CasP project.

Strategic Sabotage

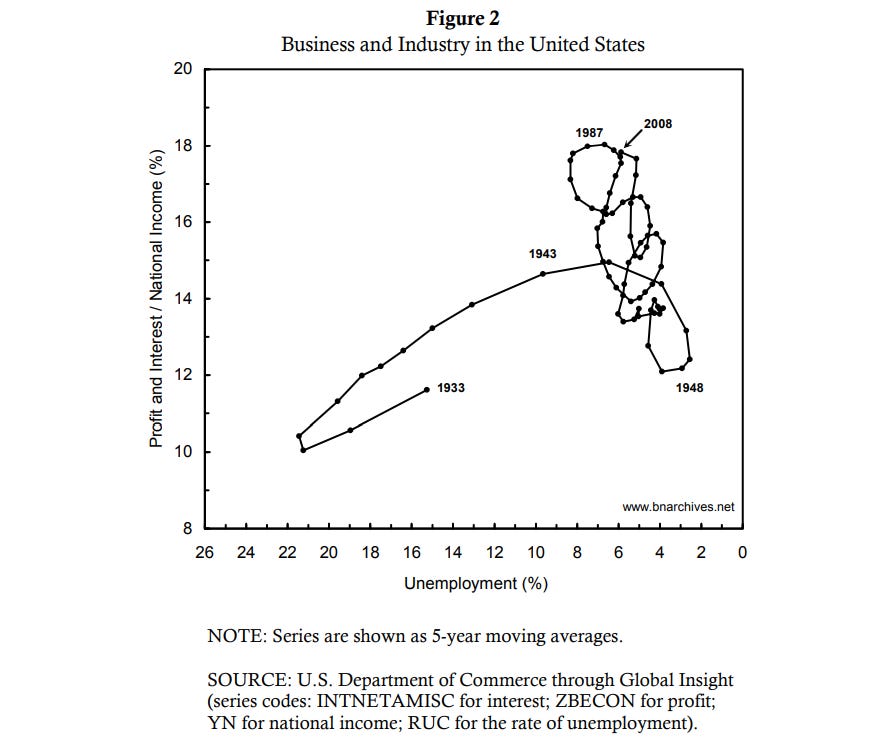

Strategic sabotage suggests that one staple of both mainstream and Marxian economists is incorrect, that greater output leads to greater profits. In contrast, it suggests that due to the tight labor markets associated with higher employment and higher output, such conditions actually lead to lower profits after a certain point. And, crucially, this is a secular, not cyclical phenomena (it is after all, well documented that late in the business cycle it is typical to have falling profits and tight labor markets). They formalize this by proposing a theory where the relationship between profits and unemployment is that of a parabolic curve rather than the normal linear one.

They provide empirical data that seems to back up this theory by comparing profit and interest as a share of national income and unemployment on a scatter plot, with the variables being recorded as 5 year moving averages.

To see if this is truly the case, I attempted to replicate these results. Unfortunately, I do not have access to Global Insight where they retrieved this data, but equivalent national account data provided by the Bureau of Economic Analysis should be available through the Federal Reserve.

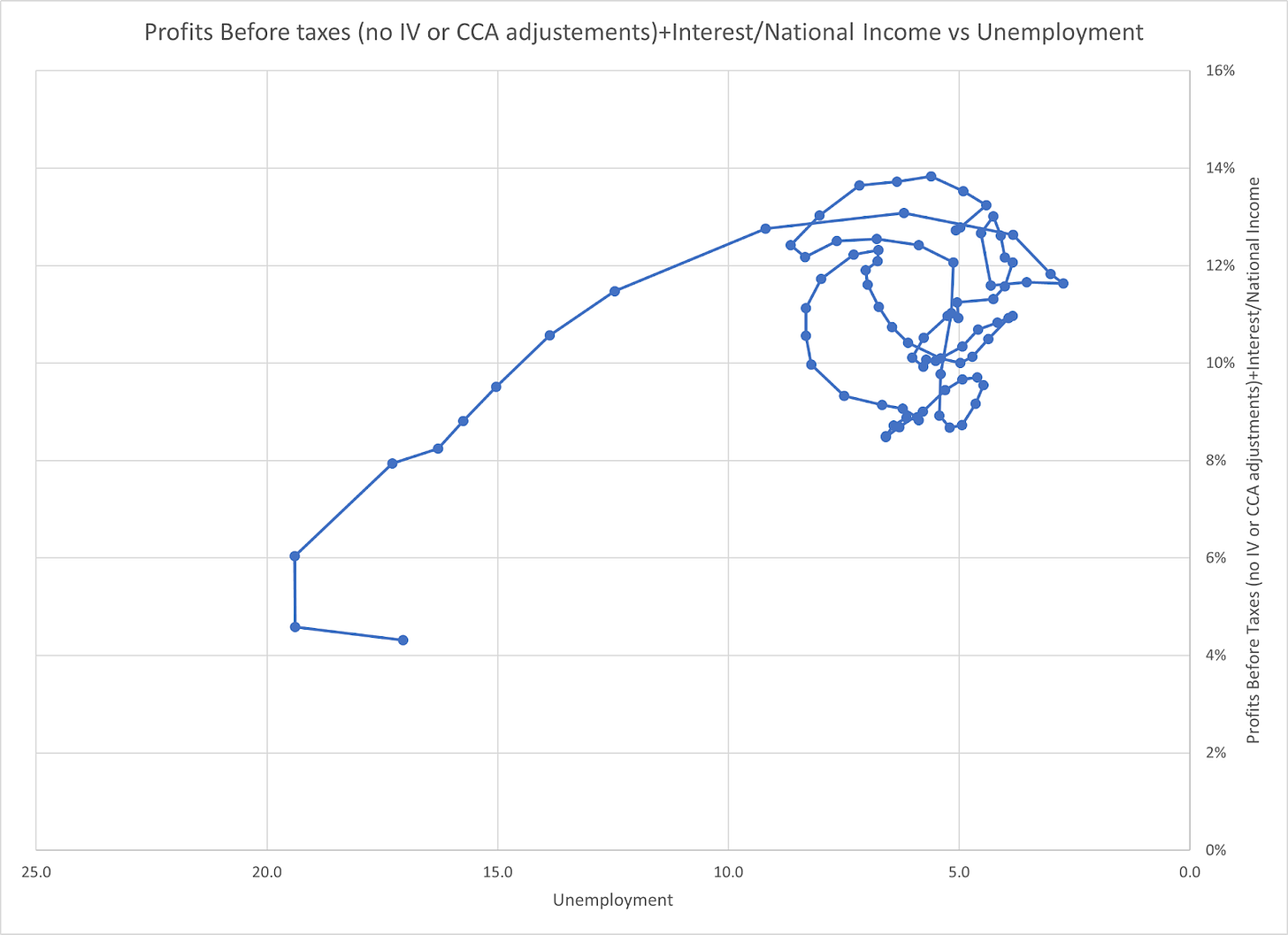

I put together the same scatter plot using multiple metrics for profit, including Net Operating Surplus, Profits Before Tax, and Profits After Tax both with and without inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments, using the same 5 year moving average methodology, however the results were far less conclusive.

Out of the five metrics of profit, only two seemed similar to what Bichler and Nitzan found: Profits before taxes with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments, and profits after taxes without inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments.

Compared to the original, it’s far more ambiguous whether a polynomial or linear trend line would be more appropriate, but more important is the fact that it appears whether there is any case for a parabolic relationship is dependent on both whether the data is pre or post taxes, as well as whether inventory valuation and constant capital adjustments have been made. Note that it would be much more supportive to Bichler and Nitzan’s case if either only taxes mattered or only constant capital adjustments mattered, the fact that both seem to influence how linear the data is suggests that their results are driven by statistical aberrations. See the corresponding profits after taxes with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments, and profits before taxes without adjustments.

Inventory valuation adjustments are due to removing capital gains like changes in the values of inventory while held by retailers and wholesalers, and capital consumption adjustments are used to convert measures of depreciation that are based on historical-cost accounting—such as the capital consumption allowances reported on tax returns—to NIPA measures of private consumption of fixed capital that are based on current cost with consistent service lives and with empirically based depreciation schedules. CasP theory says that it is the financial rituals of the capitalist class which structures society, which suggests that the unadjusted, after-tax profit metric is their best case.

However, what goes unexplained is exactly why they chose to use a 5 year moving average. Such aggregation is certainly not an inherent part of capitalist self understanding of their economic reality, especially considering that the most acute impacts of tight labor markets are cyclical. A moving average is commonly used to see trends in a time series, the fact that it's being used in a scatter plot is somewhat suspect as the period of averaging can be adjusted to achieve the desired result. Removing the 5 year moving average absolutely eliminates the parabolic trend.

We can avoid all these troubles of aggregation and statistical adjustments by simply looking at net operating surplus instead of profit+interest. Net operating surplus is the larger category from which all these variations are divided from, including profit, interest, and things like intellectual property rents. It also happens to be extremely clear on a firm’s income statement, and valuable to owners and managers because of that clarity. In the case of the net operating surplus scatter plot, there is no variation caused by aggregation, the trend is linear regardless.

Source: profit/national income.

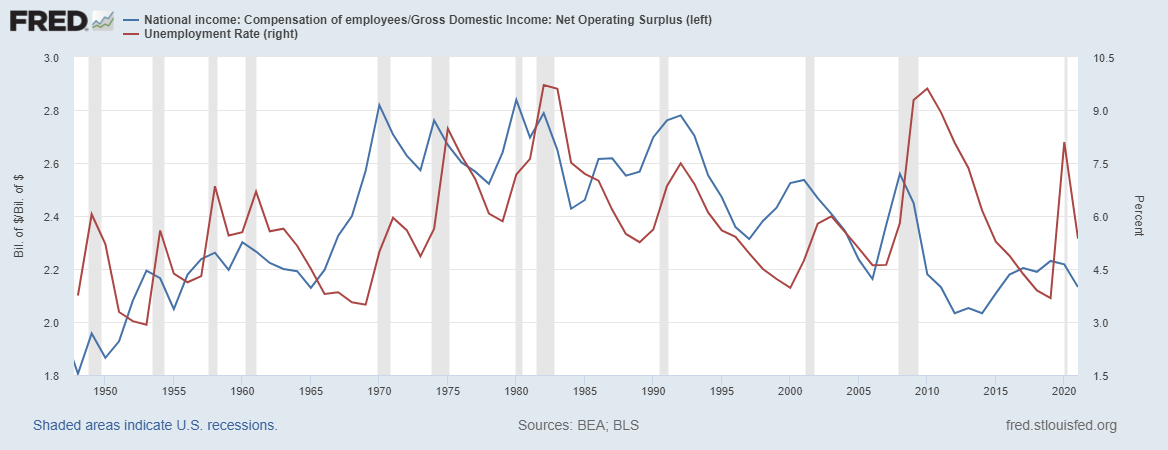

There’s very good reason to expect that net operating surplus and unemployment should have a negative correlation which goes back to Marx’s idea of surplus. The costs for reproducing the working class are essentially fixed, changing only with changing consumption habits and economic development changing the technical requirements for reproducing the household. In order to generate profit, workers must produce an output greater than the requirements for their own reproduction. Hence, the greater the output, the greater the potential surplus. It is true that changes in the rate of exploitation, the ratio of capital to labor income, can occur due to a class struggle for power, but this is not the same mechanism as the tightening of labor markets as described by Bichler and Nitzan. In fact, if we look historically, we can see that the secular rise in unemployment up until 1980 coincided with a rise in labor income relative to capital income, while the decline in unemployment from 1981 to 2007 coincided with a fall in relative labor income. This is the exact opposite of what the strategic sabotage thesis would suggest.

The Idealism of CasP Theory

What the CasP theorists fundamentally do not understand, despite all their emphasis on the ritualistic and ideological nature of capitalist structures, is that there is a material reality behind all this, that ideology and even “raw power” cannot mold in just any way they wish, and not just because the powerful are opposed by the will of some other people. Numbers on a spreadsheet can’t put food in mouths on their own. Capitalization, financial accumulation, these things can influence how surplus is allocated among the capitalist class, but only material production can create that surplus, whether it is of calories, or luxury items, or services.

At the beginning of their 2010 paper, Bichler and Nitzan cite Marx from The German Ideology to say that ideology is a force which is not only a framework for understanding reality, but one which structures and actively creates society. This is correct, but what they miss is that this active role for ideology isn’t a direct realization of the content of ideology. This itself is idealism, the idea that ideas structure our material reality and not that it is material reality that is structuring our ideas. Ideology performs a functional role in society, in getting people to reproduce the relations of production, getting people willing to go into work, to obey the state, ect.

The capitalist class too has to reproduce itself, and this is why it’s so important to distinguish Capital from the capitalist class with their inherent desire for financial accumulation and “beating the market” in terms of returns. Marx outlines the logic of capital according to the relationship of machines and tools used in production to “living labor” of actual workers, he does this because what made capitalism unique, what made it capable of taking over the world, was its revolutionizing of material production, which was chiefly accomplished by socializing labor and integrating it with the accumulation physical capital that could expand output, if not value. The logic of capital described how, because labor time was the source of value/revenue for industries, there was a constant incentive to expand output by either increasing labor time or making it more productive. When capitalists hit the limits of expanding the working day, first physically and then politically, they used machines to make production more productive, machines they had to invest in to acquire.

The investment of fixed capital is so fundamentally different from the financial investment so focused on by the CasP theorists, and much more important to the capitalist class as a whole. The logic of capital, as an ideal economic phenomena, was the ever increasing accumulation of fixed capital and the socialization of production. But this isn’t actually in the interests of the capitalist class, as a collective or individuals. More socialized production means more capitalist losers with the rise of monopolies. The Kalecki profit equations tell us that more investment as a share of profit means less money available for capitalist consumption. Relative financial accumulation can ensure the wealth of particular capitalists, but it can’t expand the amount of surplus available for capitalist consumption. Unlike low unemployment, the expansion of fixed capital investment as a share of surplus, driven by competition and technical conditions in industries, is a threat to profit.

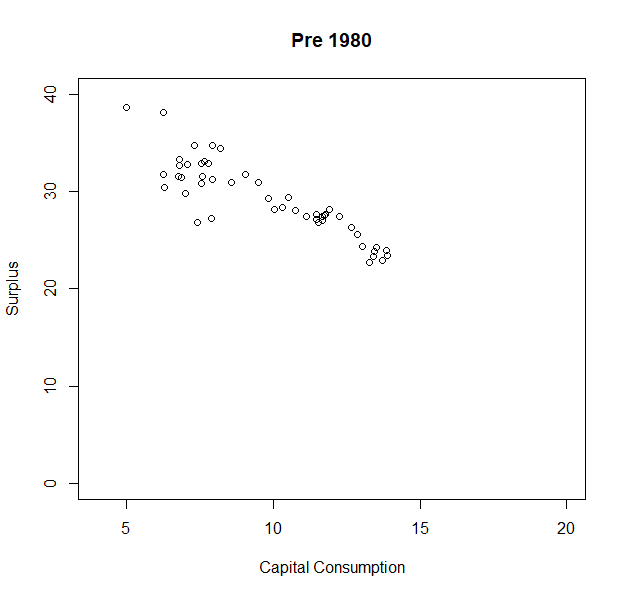

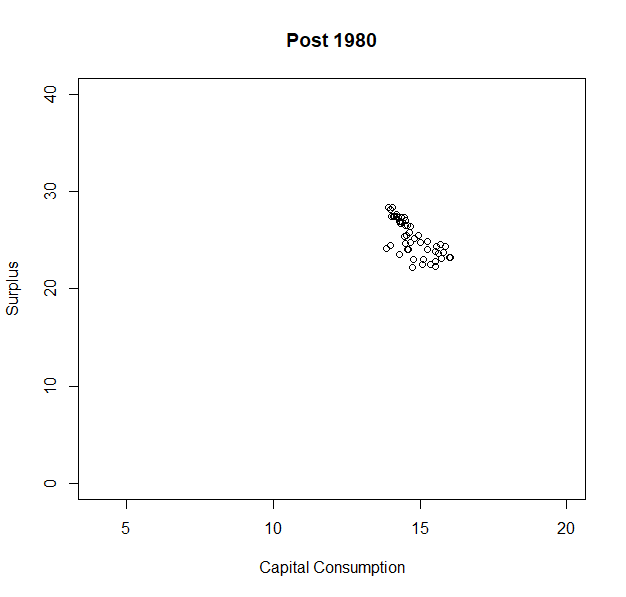

These graphs show the fundamental difference between a regime of the logic of capital up until 1980, versus a regime of the logic of capitalists after 1981. We can confirm this relationship with my rate of profit simulation1, which allows us to decompose the effect of investment decisions on the one hand, and the struggle between labor and capital for share of income on the other. Plugging in the annual rate of capitalist consumption (the inverse of the rate of capitalist investment) from the data above, and assuming a fixed rate of exploitation at its average real world level, we get a perfectly linear relationship between capital consumption and surplus, just like what we see before 1980, as well as a rate of profit not too dissimilar from what we empirically observe.

In comparison, we can look at what happens if we hold capitalist consumption rate fixed at an average level and use real world rate of exploitation data.

In this case, we see the same kind of relationship of post-1980 data for surplus and capital consumption.

Running a simulation that uses both the rate of capitalist consumption and rate of exploitation data gives us a result that follows the same pattern as the empirical data on surplus vs capital consumption.

By finding the difference between the set of capital consumption and surplus values in each of the respective simulations compared to the real world data and averaging the differences, we can get an idea of which variable is more responsible for the relationship of surplus and capital consumption as shares of national income.

For example in 1934:

Capital Consumption/National Income was 13%

The equivalent value in the simulation was 10%

The difference is 3.

Doing this for each year and also for Surplus/National Income and average the results gives us the following summary:

Source: Rate of Capitalist Consumption

Excel File with simulation data output and comparison

As you can see, changes in the rate of capitalist consumption (or the rate of capitalist investment) produce outputs in the simulation 30-50% closer to reality than changes in the rate of exploitation. This indicates that capitalist consumption and investment is primarily responsible for driving the relationship between surplus and capital consumption (aka depreciation). It isn’t a pure struggle for power as financial accumulation which is determining profits, especially not through the labor market and strategic sabotage. Instead, it is the decisions regarding physical, real investment which determine profits, and it is this impact over the material world which actual class struggle is concerned with.

The logic of capitalists, contrary to CasP, is a regime not of purely ideological formations being enforced upon society, but a change in the material realities of production. When the logic of capital prevails there is industrialization, capital deepening, and an increasing amount of investment as a share of surplus. The neoliberal era has marked a reversal of that, for the primary purpose of protecting the reproduction of the capitalist class by decreasing investment as a share of surplus, atomizing production, and stalling productivity.

But in order to come to these conclusions one needs a theory of value and prices, of capital as a material thing being reproduced rather than as an appearance or ritual. CasP theory prides itself in its lack of these things, and instead retreats into ad hoc conjectures and the casual empiricism of mainstream political science. This may be good enough to explain many of the quirks of relative accumulation in finance, but many of its claims that move beyond that, both qualitative and quantitative, suffer under scrutiny as a result.

One important adjustment I had to make to this simulation was to make it so that the rate of capitalist consumption applied to a definition of profit that included consumption of fixed capital (aka depreciation) in order to effectively follow the Kalecki profit equations. I’ll have a follow up post on this correction soon. The updated model can be found here profitratesim/profitsim10.25 at main · nicosims/profitratesim (github.com)